Click the link to read the article on the High Country News website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

September 23, 2025

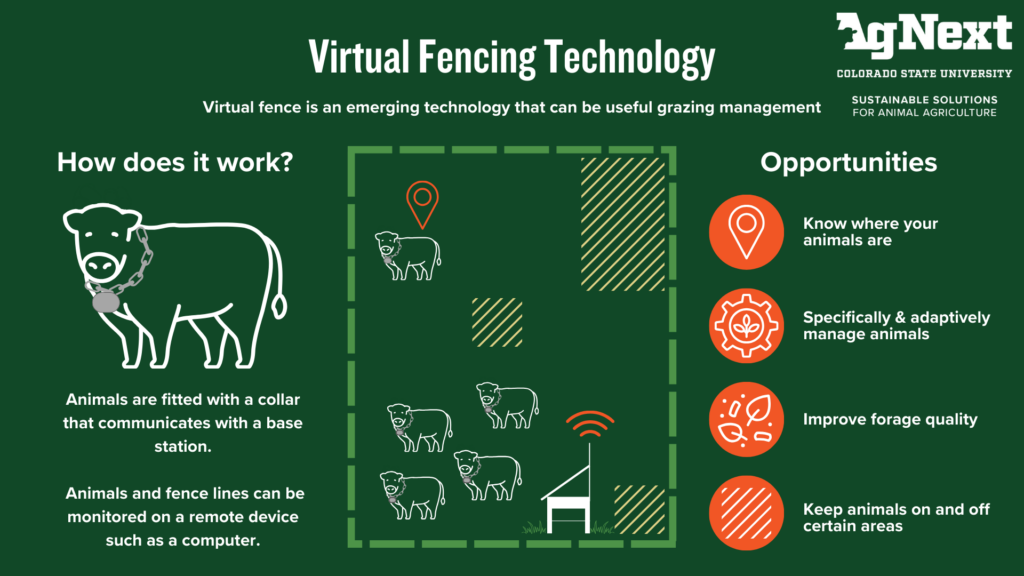

In the 1880s, giant cattle companies turned thousands of cattle out to graze on the “public domain” — i.e., the Western lands that had been stolen from Indigenous people and then opened up for white settlement. In remote southeastern Utah, this coincided with a wave of settlement by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The region’s once-abundant grasslands and lush mountain slopes were soon reduced to denuded wastelands etched with deep flash-flood-prone gullies. Cattlemen fought, sometimes violently, over water and range.

The local citizenry grew sick and tired of it, sometimes literally: At one point, sheep feces contaminated the water supply of the town of Monticello and led to a typhoid outbreak that killed 11 people. Yet there was little they could do, since there were few rules on the public domain and fewer folks with the power to enforce them.

That changed in 1891, when Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act, which authorized the president to place some unregulated tracts under “judicious control,” thereby mildly restraining extractive activities in the name of conservation. In 1905, the Forest Service was created as a branch of the U.S. Agriculture Department to oversee these reserves, and Gifford Pinchot was chosen to lead it. And a year later, the citizens of southeastern Utah successfully petitioned the Theodore Roosevelt administration to establish forest reserves in the La Sal and Abajo Mountains.

Since then, the Forest Service has gone through various metamorphoses, shifting from stewarding and conserving forests for the future to supplying the growing nation with lumber to managing forests for multiple uses and then to the ecosystem management era, which began in the 1990s. Throughout all these shifts, however, it has largely stayed true to Pinchot and his desire to conserve forests and their resources for future generations.

But now, the Trump administration is eager to begin a new era for the agency and its public lands, with a distinctively un-Pinchot-esque structure and a mission that maximizes resource production and extraction while dismantling the administrative state and its role as environmental protector. Over the last nine months, the administration has issued executive orders calling for expanded timber production and rescinding the 2001 Roadless Rule, declared “emergency” situations that enable it to bypass regulations on nearly 60% of the public’s forests, and proposed slashing the agency’s operations budget by 34%.

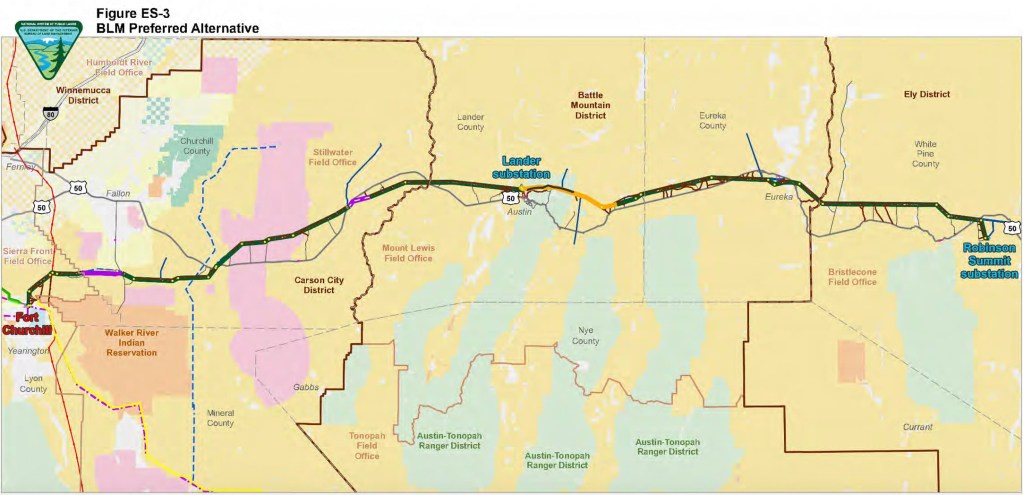

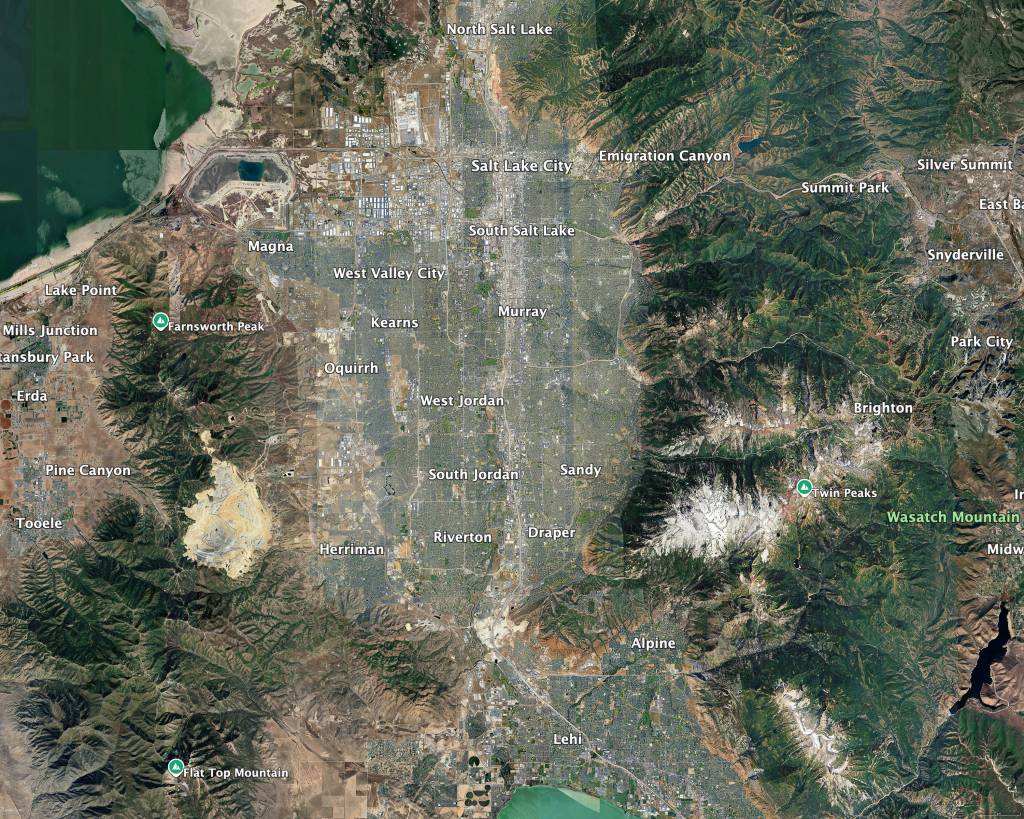

The most recent move, which is currently open to public comment, involves a proposal by Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins to radically overhaul the entire U.S. Department of Agriculture. Its stated purposes are to ensure that the agency’s “workforce aligns with financial resources and priorities,” and to consolidate functions and eliminate redundancy. This will include moving at least 2,600 of the department’s 4,600 Washington, D.C., employees to five hub locations, with only two in the West: Salt Lake City, Utah, and Fort Collins, Colorado. (The others will be in North Carolina, Missouri and Indiana.) The goal, according to Rollins’ memorandum, is to “bring the USDA closer to its customers.” The plan is reminiscent of Trump’s first-term relocation of the Bureau of Land Management’s headquarters to Grand Junction, Colorado, in 2019. That relocation resulted in a de facto agency housecleaning; many senior staffers chose to resign or move to other agencies, and only a handful of workers ended up in the Colorado office, which shared a building with oil and gas companies.

Though Rollins’ proposal is aimed at decentralizing the department, it would effectively re-centralize the Forest Service by eliminating its nine regional offices, six of which are located in the West. Each regional forester oversees dozens of national forests within their region, providing budget oversight, guiding place-specific implementation of national-level policies, and facilitating coordination among the various forests.

Rollins’ memo does not explain why the regional offices are being axed, or what will happen to the regional foresters’ positions and their functions, or how the change will affect the agency’s chain of command. When several U.S. senators asked Deputy Secretary Stephen Vaden for more specifics, he responded that “decisions pertaining to the agency’s structure and the location of specialized personnel will be made after” the public comment period ends on Sept. 30. Curiously, the administration’s forest management strategy, published in May, relies on regional offices to “work with the Washington Office to develop tailored strategies to meet their specific timber goals.” Now it’s unclear that either the regional or Washington offices will remain in existence long enough to carry this out.

The administration has been far more transparent about its desire to return the Forest Service to its timber plantation era, which ran from the 1950s through the ’80s. During that time, logging companies harvested 10 billion to 12 billion board-feet per year from federal forests, while for the last 25 years, the annual number has hovered below 3 billion board-feet. Now, Trump, via his Immediate Expansion of American Timber Production order, plans to crank up the annual cut to 4 billion board-feet by 2028. This will be accomplished — in classic Trumpian fashion — by declaring an “emergency” on national forest lands that will allow environmental protections and regulations, including the National Environmental Protection Act, Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act, to be eased or bypassed.

In April, Rollins issued a memorandum doing just that, declaring that the threat of wildfires, insects and disease, invasive species, overgrown forests, the growing number of homes in the wildland-urban interface and more than a century of rigorous fire suppression have contributed to what is now “a full-blown wildfire and forest health crisis.”

Emergency determinations aren’t limited to Trump and friends; in 2023, the Biden administration identified almost 67 million acres of national forest lands as being under a high or very high fire risk, thus qualifying as an “emergency situation” under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Rollins, however, vastly expanded the “emergency situation” acreage to almost 113 million acres, or 59% of all Forest Service lands. This allows the agency to use streamlined environmental reviews and “expedited” tribal consultation time frames to “carry out authorized emergency actions,” ranging from commercial harvesting of damaged trees to removing “hazardous fuels” to reconstructing existing utility lines. Meanwhile, the administration has announced plans to consolidate all federal wildfire fighting duties under the Interior Department. This would completely zero out the Forest Service’s $2.4 billion wildland fire management budget, sowing even more confusion and chaos.

The administration also plans to slash staff and budgets in other parts of the agency, further compromising its ability to carry out its mission. The so-called “Department of Government Efficiency,” or DOGE, fired about 3,400 Forest Service employees, or more than 10% of the agency’s total workforce, earlier this year. And the administration has proposed cutting the agency’s operations budget, which includes salaries, by 34% in fiscal year 2026, which will most likely necessitate further reductions in force. It would also cut the national forest system and capital improvement and maintenance budgets by 21% and 48% respectively.

The goal, it seems, is to cripple the agency with both direct and indirect blows. The result, if the administration succeeds, will be a diminished Forest Service that would be unrecognizable to Gifford Pinchot.