Click the link to read the article on the Center for Colorado River Studies website (Jack Schmidt[1], Eric Kuhn[2], Anne Castle[3], Kathryn Sorensen[4], Katherine Tara[5]):

February 9, 2026

Key Points

- The rules that control releases from Lake Powell and Lake Mead are very different. Lake Powell’s releases are determined by an Annual Operating Plan that has little flexibility during the year. Lake Mead’s releases change each month in response to changing delivery requirements to Lower Basin users. The impact of these different release rules on each reservoir’s storage was illustrated this autumn and early winter when Lake Powell steadily declined and Lake Mead steadily increased. The magnitude of Powell’s decline and Mead’s increase compensated for one another, and the total combined storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead did not change.

- During the four months between October 1 and February 1, Lake Mead’s releases were reduced in response to decreasing Lower Basin demands, but Lake Powell’s releases were not similarly reduced. Lake Powell lost 615,000 af during the four-month study period, and Lake Mead gained the same amount.

- On February 1, Lake Mead had 2,714,000 af more water than Lake Powell, the largest difference between the two reservoirs since April 2022.

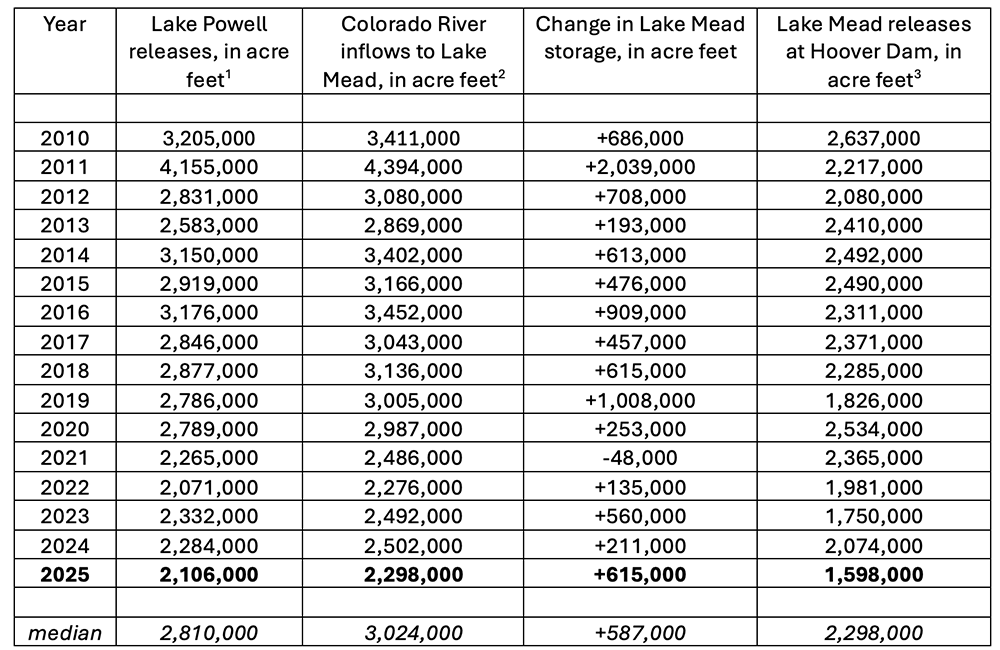

- Modest flood inflows in early October delayed drawdown of Lake Powell by six weeks. Releases during the four-month study period were the second smallest since at least 2010[1]. Releases from Lake Mead were the smallest since at least 2010. Despite the small inflows to Lake Mead, the increase in storage in Lake Mead during the study period was the largest since 2019.

- The four-month delay in depletion of the combined storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead saved between 400,000 to 900,000 af.

- Forecasts for spring snowmelt inflow to Lake Powell are not encouraging and have been declining all winter, because Rocky Mountain snowpack remains meager.

[1]We compared the inflows, outflows, changes in storage, and Lower Basin consumptive uses between 2010 and 2026.

Briefly

In mid-September 2025, we noted that if the 2026 snowmelt was as little as in 2025, the total realistically accessible combined storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell reservoirs (hereafter referred to as Powell+Mead) would likely fall to less than 4 million acre-feet (af) by early autumn 2026, less than the 21st century minimum of March 2023. At the mid-point of winter 2025-2026, where do we stand?

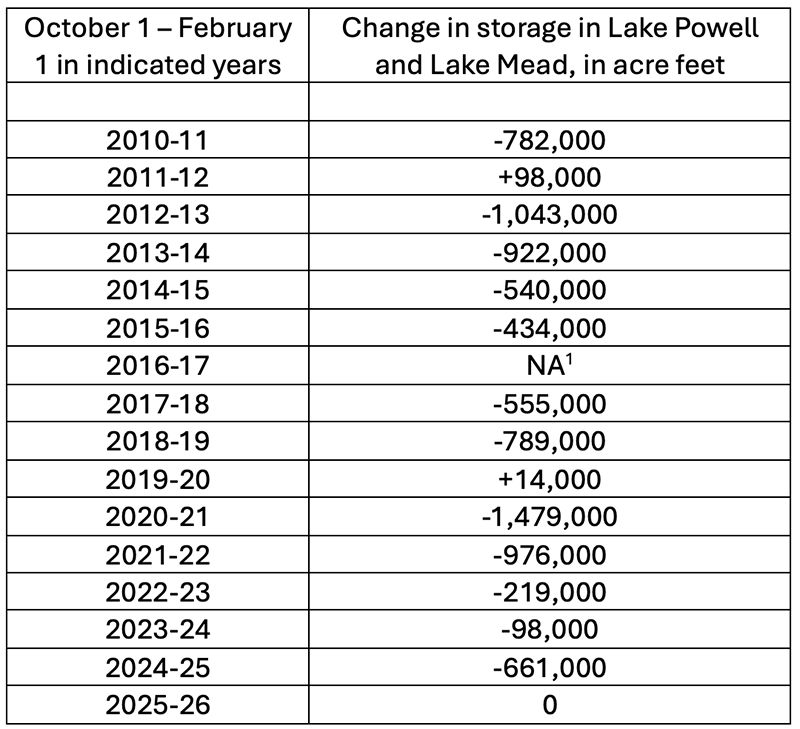

Despite the bad news associated with this winter’s meager Rocky Mountain snowpack and the prospect of insignificant spring inflow to Lake Powell, unusually large autumn rainfall, alongside involuntary shortages and compensated system conservation efforts, reduced the need for deliveries to Lower Basin users, resulting in a significant increase in storage in Lake Mead that matched the drawdown of Lake Powell. As a result, total combined storage In Powell+Mead did not change in October, November, December, and January[1]. This is a helpful and important outcome.

Total inflow to Lake Powell and from sources between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead totaled 1.72 million af during the four-month study period (Table 1). Outflows from Lake Mead, including consumptive use by Nevada and estimated evaporation losses from Lake Powell and Lake Mead, were 1.75 million af. Because the combined storage of Powell+Mead did not change, the Inflows and the outflows, including losses must have been equal. The small discrepancy between inflows and outflows from this two-reservoir system (last two rows of Table 1) remind us of the inherent uncertainty and imprecision of some measurements. In this case, the sources of uncertainty include unmeasured inflows, unmeasured gains and losses of bank storage, and uncertainty in measurements, especially of evaporation.

1 sum of daily evaporation reported in Reclamation Hydrodata base. https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/hydrodata/reservoir_data/site_map.html

2 sum of daily evaporation reported by Lower Colorado Region, Reclamation. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/levels_archive.html.

Even though the total amount of water in Powel+Mead did not change, Lake Powell dropped and Lake Mead rose during the study period resulting in transfer of water from Lake Powell to Lake Mead. Lake Powell lost 615,000 af during the four-month study period, and Lake Mead gained the same amount. Autumn rains modestly augmented inflows to Lake Powell, and Reclamation significantly reduced releases at Hoover Dam, such that inflows and outflows to Powell+Mead approximately balanced each other.

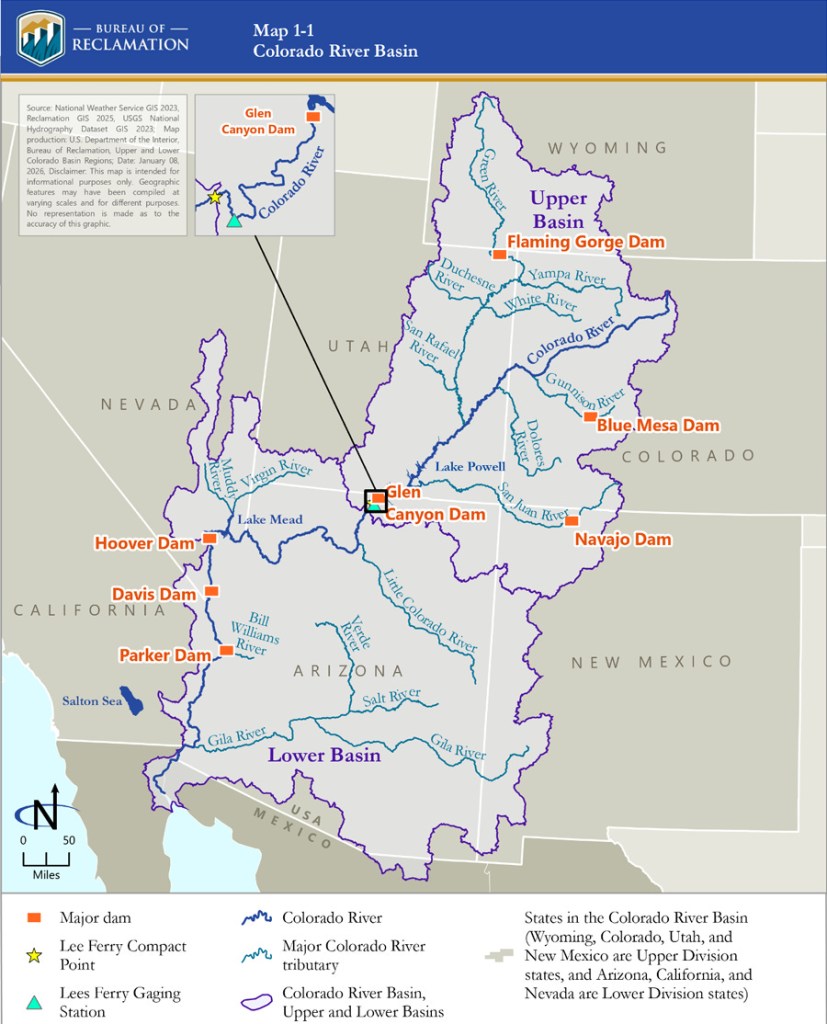

On February 1, Lake Mead had 2,714,000 af more water than Lake Powell, the largest difference between the two reservoirs since April 2022[2] (Fig. 1). Divergence in the amount stored in each reservoir resulted from different operating rules. Releases from Lake Powell in the Upper Basin are established in an Annual Operating Plan intended to meet the Upper Basin’s delivery obligation to the Lower Basin. This plan has little flexibility to adjust releases in response to unexpected changes in inflow. In contrast, releases from Lake Mead are adjusted to the changing delivery requirements to Lower Basin users. As demand in the Lower Basin decreased in autumn and early winter, releases from Lake Mead were significantly reduced.

Details

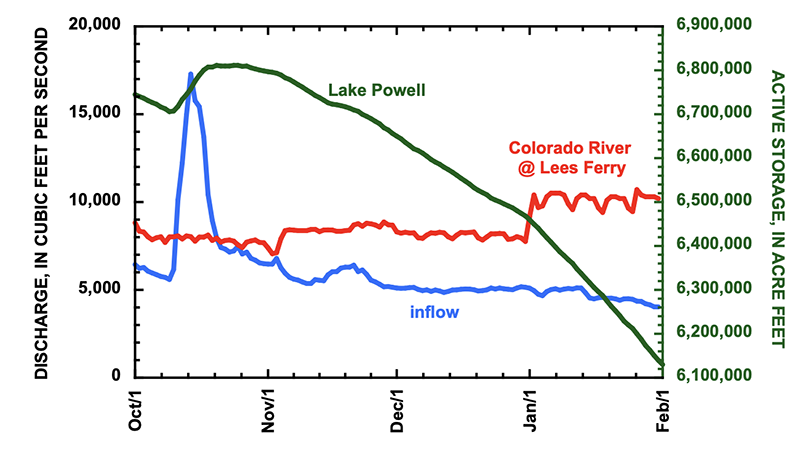

Although October flood inflows to Lake Powell were modest, this short period of augmented inflow delayed the long-term decline in storage by six weeks, an important respite for the reservoir. Inflow to Lake Powell from the Colorado River, the largest source of inflow, was only 75% of average in November, December, and January but exceeded the three-year average between October 12 and 19[3]. Inflow from the San Juan River, the second largest inflow source, exceeded the long-term daily average between October 11 and 22 and between November 15 and 24[4]. As a result, storage in Lake Powell increased by 105,000 af between October 9 and 20, the period when inflow exceeded reservoir release (Fig. 2). The rate of subsequent reservoir decline was much slower than the initial rise, and it was not until late November that Lake Powell returned to the elevation it had been just before the onset of the October floods.

The drop in Lake Powell that began in late October occurred despite Reclamation’s decision to delay release of approximately 600,000 af until summer 2026.[5] Total release from Lake Powell during the study period was 2.106 million af, the second smallest fall and early winter release since 2010 (Table 2).

1Colorado River at Lees Ferry

2Colorado River above Diamond Creek near Peach Springs

3Reclamation, Lower Basin Accounting Reports. Hydrodata for 2025-26.Reclamation reduced releases from Lake Mead beginning in mid-November. In response, storage increased, because inflows exceeded releases (Fig. 3). Recovery of Lake Mead during these months was the largest since 2019 and was 5% greater than the median autumn and early winter recovery since 2010 (Table 2). Releases from Lake Mead were the smallest since at least 2010 and were 30% less than the median total release for those years. The increase in Lake Mead occurred despite the small releases from Lake Powell.

The small demand for water from Lake Mead was due to a combination of significantly reduced agricultural demand caused by abundant autumn precipitation in California’s Imperial and Coachella Valleys, the Yuma area, and elsewhere in Arizona and southeastern California as well as ongoing Lower Basin programs including involuntary shortage cuts (mostly) to Arizona, Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) contributions, and reductions in water use from compensated system conservation. Although agricultural consumptive use in Arizona and the Imperial Valley is always smallest between November and February, demand in fall 2025, especially in November, was unusually small (Table 3). Withdrawal of water by the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD) into the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal and consumptive use by the Imperial Irrigation District (IID) in November 2025 was less than in any previous November since at least 2010 and was 26% and 54% of the median November use[6], respectively, by those districts. Consumption in October and November by other Arizona users of mainstem Colorado River water was the second smallest since at least 1979 and CAWCD use in October was the second smallest since 1995. Only in 2024 was use less. Use by the Metropolitan Water District in January was the second smallest of the study period.

1Lowest monthly use since at least 2010

2 Second lowest monthly use since at least 2010

3Median monthly use computed for 2010-2026A Bit of a Silver Lining

What was the significance of the four-month delay in depletion of Powell+Mead? Combined Powell+Mead storage increased between October 1 and February 1 twice since 2010, in the large runoff years of 2011 and 2019 (Table 4). In all other years, storage declined during these four months, and this year’s decrease of 200 af was the smallest decline among those 12 recent years of decline. The median drawdown of the 12 years of decline was 660,000 af and ranged between this year’s tiny drawdown and drawdown of more than 1 million af in 2012 and 2020. It is beyond the scope of this paper to estimate what the drawdown of Powell+Mead would have otherwise been, but a reasonable estimate of the water savings caused by the delayed drawdown of Powell+Mead this year is between 400,000 to 900,000 af[7]. To this small degree, the autumn rains and programs and policies to reduce Lower Basin demand allowed the Basin’s water managers to take one small step back from the edge of the cliff.

1The combined contents of Lake Powell and Lake Mead began to increase on January 13, 2016. Between October 1 and January 13, the two reservoirs lost 655,000 af.

But, the Bad News

Bad news looms in the future, especially for Lake Powell. The January 2026 24-Month Study’s most probable forecast predicts that in March 2027, storage in Lake Powell will drop to 4,382,000 af of active storage, of which only 150,000 af is realistically accessible (3 ft above reservoir elevation 3500 ft).[8] When Lake Powell is at or below elevation 3500 ft, reservoir releases are complicated by the risk of cavitation in the Glen Canyon Dam turbines and the inability to constantly use the river outlet works. Under the minimum probable inflow forecast, the predicted elevation of Lake Powell is 3476 ft in March 2027, an elevation in which no water could be released through the penstocks and no hydropower would be produced.

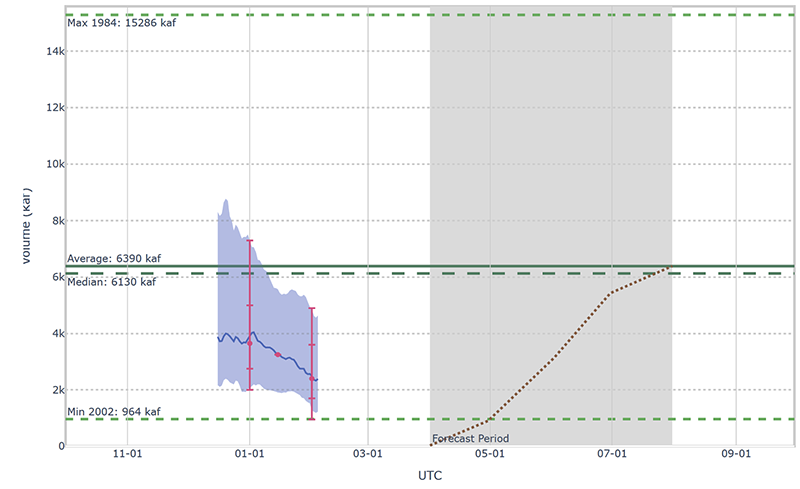

Even the minimum probable forecast may be overly optimistic, because the forecast for April – July unregulated inflow to Lake Powell has been progressively decreasing, because the winter’s snowpack remains meager. The Colorado River Basin Forecast Center’s official February 1 forecast is that the 50th percentile prediction (considered the most probable forecast) is 2.4 million af, significantly less than the January forecast of 3.65 million af (Fig. 4). The 90th percentile prediction (considered the minimum probable forecast) has dropped from 2.1 million af to 950,000 af. If the actual unregulated inflow were to be that of the minimum probable forecast, 2026 would replace 2002 as the lowest April to July inflow on record. Reclamation’s February 24-Month Study will be released in mid-February, and those results will certainly draw considerable attention.

Unless the snowpack significantly improves between now and early April, Reclamation will have difficult choices to make. Ideally, the agency could use a combination of a large release from Flaming Gorge Reservoir coupled with an additional reduction in releases from Lake Powell to keep the elevation of Lake Powell above 3500 ft. Unless Flaming Gorge Reservoir releases are implemented using the Secretary of the Interior’s emergency authority, however, consultation and agreement with the Upper Basin states will be required. This was the strategy used in 2022, and Reclamation has indicated that even with a release of water from upstream reservoirs, there may still be a need for reductions in Lake Powell releases.[9] However, if the annual release from Lake Powell is reduced to 7 million af or less, the 10-year delivery of water from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin will be less than what some states consider the delivery obligation of the Upper Basin (i.e., the Compact tripwire). In such a circumstance, interstate litigation might ensue.

Until basin-wide uses are reduced to meet the available supply, there are no good choices!

[1] Combined active storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell was 14,974,197 on October 1, 2025. Combined storage on February 1, 2026, was 14,973,991af.

[2] The disparity between storage in the two reservoirs has continued to increase. On February 8, Lake Mead had 2,810,000 af more water in storage than Lake Powell.

[3] Average flow of the Colorado River at Gypsum Canyon near Hite was calculated between June 30, 2023, and January 31, 2026. https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/USGS-09328960/statistics/.

[4] Average flow of the San Juan River near Bluff was calculated between October 30, 1914, and January 31, 2026. https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/USGS-09379500/statistics/.

[5] The goal of delayed release was to protect a target elevation at Lake Powell of 3525 feet. Adjustments to Glen Canyon Dam monthly releases were adjusted to hold back 598,000 af in Lake Powell between December 2025 and April 2026 (Reclamation, January 2026 24-Month Study). https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/24mo.pdf.

[6] 2010-2025

[7] This is the interquartile range of the 12 years when Powell+Mead declined in storage.

[8] For an explanation of “realistically accessible storage” see Schmidt et al., Analysis of Colorado River Basin Storage Suggests Need For Immediate Action, Sep. 11, 2025, https://www.inkstain.net/2025/09/analysis-of-colorado-river-basin-storage-suggests-need-for-immediate-action/.

[9] Reclamation, 2024 SEIS ROD: Section 6(E) Monthly Meeting, Jan. 22, 2026.Authors:

[1] Director, Center for Colorado River Studies, Utah State University, former Chief, Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center.

[2] Retired General Manager, Colorado River Water Conservation District.

[3] Getches-Wilkinson Center, University of Colorado Law School, former US Commissioner, Upper Colorado River Commission, former Assistant Secretary for Water and Science, US Dept. of the Interior.

[4] Kyl Center for Water Policy, Arizona State University, former Director, Phoenix Water Services.

[5] Staff Attorney, Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico.