Click the link to read the article on the Water Education Colorado website (Shannon Mullane):

May 22, 2025

Denver, Aurora, Colorado Springs and Northern Water voiced opposition Wednesday to the Western Slope’s proposal to spend $99 million to buy historic water rights on the Colorado River.

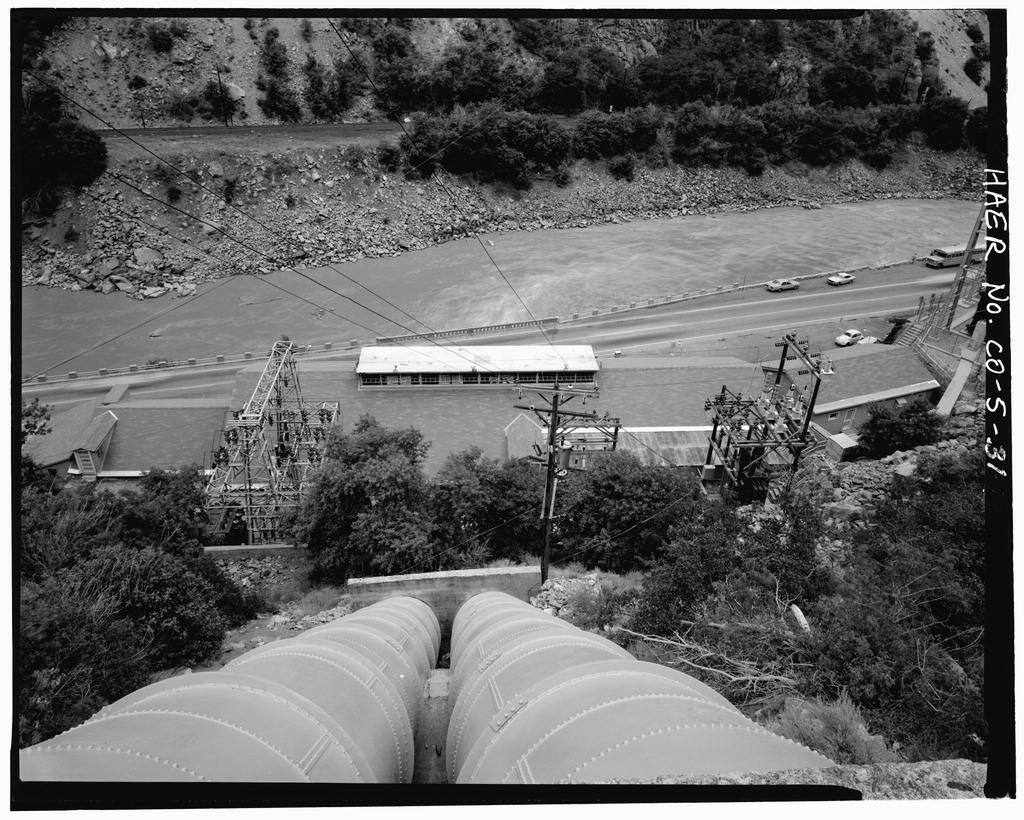

The Colorado River Water Conservation District has been working for years to buy the water rights tied to Shoshone Power Plant, a small, easy-to-miss hydropower plant off Interstate 70 east of Glenwood Springs. The highly coveted water rights are some of the largest and oldest on the Colorado River in Colorado.

The Front Range providers are concerned that any change to the water rights could impact water supplies for millions of people in cities, farmers, industrial users and more. The Front Range providers publicly voiced their concerns, some for the first time, at a meeting of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, a state water policy agency.

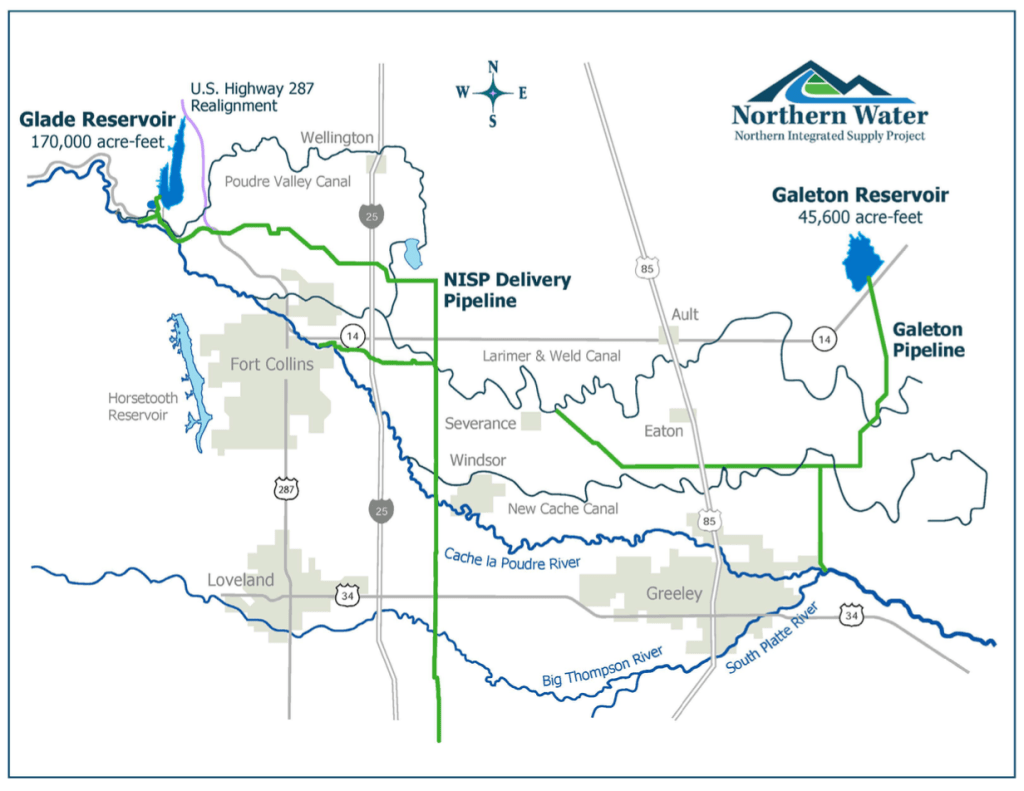

The proposed purchase taps into a decades-old water conflict in Colorado: Most of the state’s water flows west of the Continental Divide; most of the population lives to the east; and water users are left to battle over how to share it.

“If this proposal were to go forward as presented in the application, it could harm our ability to provide water for essential use during severe or prolonged drought. I think it’s important for the board to understand that,” Jessica Brody, an attorney for Denver Water, told the 15-member board Wednesday.

Denver Water, the oldest and largest water provider in Colorado, delivers water to 1.5 million residents in the Denver area.

The Colorado River District, which represents 15 Colorado counties west of the Continental Divide, wants to keep the status quo permanently to support river-dependent Western Slope economies without harming other water users, district officials said.

The overstressed and drought-plagued river is a vital water source for about 40 million people across the West and northern Mexico.

“That right is so important to keeping the Colorado River alive,” Andy Mueller, Colorado River District general manager, said during the meeting’s public comment period. “This is a right that will save this river from now into eternity … and that’s why this is so important.”

Over 70 people, nearly twice the usual audience, attended the four-hour Shoshone discussion Wednesday, which involved 561 pages of documents, over 20 speakers and a public comment period.

The Western Slope aims to make history

The water rights in question, owned by Public Service Company of Colorado, a subsidiary of Xcel, are some of the most powerful on the Colorado River in Colorado.

Using the rights, the utility can take water out of the river, send it through hydropower turbines, and spit it back into the river about 2.4 miles downstream.

One right is old, dating back to 1905, which means it can cut off water to younger — or junior — upstream water users to ensure it gets its share of the river in times of shortage. Some of those junior water rights are owned by Denver Water, Aurora, Colorado Springs Utilities and Northern Water.

The rights are also tied to numerous, carefully negotiated agreements that dictate how water flows across both western and eastern Colorado.

Over time, Western Slope communities have come to rely on Shoshone’s rights to pull water to their area to benefit farmers, ranchers, river companies, communities and more.

The Colorado River District wants to buy the rights to ensure that westward flow of water will continue even if Xcel shuts down Shoshone (which the utility has said, repeatedly, it has no plans to do).

They’ve gathered millions of dollars from a broad coalition of communities, irrigators and other water users. The state of Colorado plans to give $20 million to help fund the effort.

The federal government might give $40 million, but that funding was tied up in President Donald Trump’s policy to cut spending from big Biden-era spending packages. It was unclear Thursday if the awarded funds will come through, the district said.

Supporters sent over 50 letters to the Colorado Water Conservation Board before Wednesday’s meeting.

“I wanted to just convey the excitement that the river district and our 30 partners have, here on the West Slope, to really do something that is available once in a generation,” Mueller said.

The Front Range water providers all said they, too, wanted to maintain those status quo flows. They just don’t want to see any changes to the timing, amount or location of where they get their supplies.

Under the district’s proposal, the state would be able to use Shoshone’s senior water rights to keep water in the Colorado River for ecosystem health when the power plant isn’t in use.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board is tasked with deciding whether it will accept the district’s proposal for an environmental use. The meeting Wednesday triggered a 120-day decision making process.

“Any change to the rights will have impacts both intended and unintended, and it is important for the board to understand those impacts to avoid harm to existing water users,” Brody said.

The water provider plans to contest the Colorado River District’s plan within that 120-day period.

How much water is at stake?

The Front Range providers voiced another concern: The River District’s proposal could be inflating Shoshone’s past water use.

Water rights come with upper limits on how much water can be used. It’s a key part of how water is managed in Colorado: Setting a limit ensures one person isn’t using too much water to the detriment of other users.

For those who have a stake in Shoshone’s water rights — which includes much of Colorado — it’s a number to fight over.

The River District did an initial historical analysis, which calculated that Shoshone used 844,644 acre-feet on average per year between 1975 and 2003. One acre-foot of water supplies two to three households for a year.

Denver Water said the analysis ignored the last 20 years of Shoshone operations. Colorado Springs, Northern Water and Aurora questioned the district’s math. Northern was the first provider to do so publicly in August.

“We think the instream flow is expanded from its original historic use by up to 36%,” said Alex Davis, Aurora Water’s assistant general manager of water supply and demand.

She requested the board do its own study of Shoshone’s historical water use instead of accepting the River District’s analysis — which would mean the state agency would side with one side of the state, the Western Slope, against the other, Davis said.

The River District emphasized that its analysis was preliminary. The final analysis will be decided during a multiyear water court process, which is the next step if the state decides to accept the instream flow application.

Water court can be contentious and costly, Davis said.

“This could be incredibly divisive if we have to battle it out in water court, and we don’t want to do that,” Davis said.