July 25, 2025

Front Range asked for Colorado Water Conservation Board neutrality on historic use of Shoshone water rights

In an effort to head off concerns about the state’s role in a major Western Slope water deal, a Western Slope water district has offered up a compromise proposal to Front Range water providers.

In order to defuse what Colorado River Water Conservation District General Manager Andy Mueller called “an ugly contested hearing before the CWCB,” the River District is proposing that the state water board take a neutral position on the exact amount of water tied to the Shoshone hydropower plant water rights and let a water court determine a final number.

“Although we believe this would be an unusual process, the River District believes it would address the primary concern (i.e., avoiding the state agency’s formal endorsement of the River District’s preliminary historical use analysis) that we heard expressed by your representatives at the May 21, 2025 CWCB meeting regarding the Shoshone instream flow proposal,” Mueller wrote in an email to officials from the Front Range Water Council.

The River District worked with CWCB staff to draft the proposal, but it may not go far enough to address Front Range concerns.

The River District, which represents 15 counties on the Western Slope, is planning to purchase some of the oldest and largest non-consumptive water rights on the Colorado River from Xcel Energy for nearly $100 million. The water rights, which are tied to the Shoshone hydropower plant in Glenwood Canyon, are essential for downstream ecosystems, cities, endangered fish, and agricultural and recreational water users. As part of the deal, the River District is seeking to add an instream flow water right to benefit the environment to the hydropower water rights.

The effort has seen broad support across the Western Slope. The River District has raised $57 million toward the purchase from at least 26 local and regional partners. The project was awarded a $40 million Inflation Reduction Act grant in the waning days of the Biden administration, but those funds have been frozen by the Trump administration.

“These water rights are foundational to the Colorado River,” said Amy Moyer, chief of strategy at the River District. “It’s the number one project for the Western Slope. It’s the top priority to move forward.”

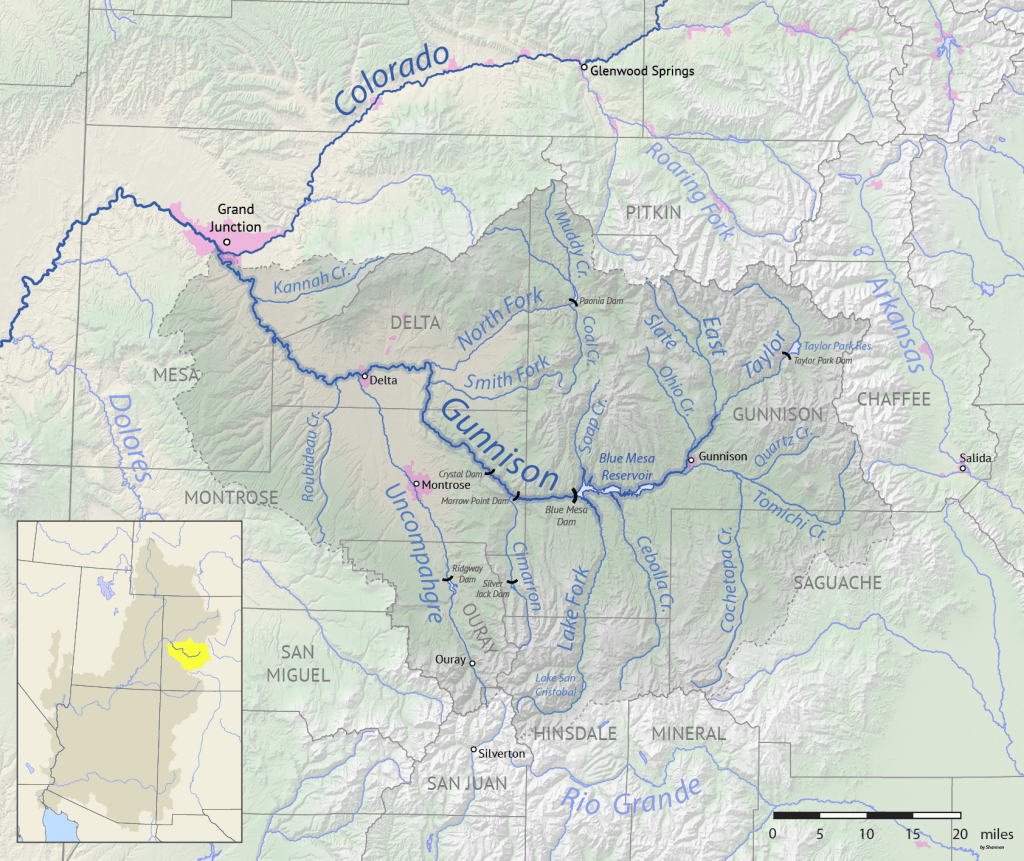

Critically, because its water rights are senior to many other water users — they date to 1902 — Shoshone can force upstream water users to cut back. The Shoshone call has the ability to command the flows of the Colorado River and its tributaries upstream all the way to the headwaters.

Putting a precise amount on how much water the plant has historically used is a main point of contention between the River District and the Front Range Water Council, a group that includes some of Colorado’s biggest municipal water providers: Denver Water, Colorado Springs Utilities, Aurora Water and Northern Water. These entities take water that would normally flow west, and bring it to farms and cities on the east side of the Continental Divide through what are called transmountain diversions. About 500,000 acre-feet of water annually is taken from the headwaters of the Colorado River and its tributaries to the Front Range.

Estimates by the River District put the Shoshone hydro plant’s average annual use at 844,644 acre-feet using the period between 1975 and 2003 — before natural hazards in the narrow canyon began knocking the plant offline regularly in recent years.

But Front Range Water Council members say this estimate is flawed and could be an expansion of the historical use of the water right. They have requested a hearing at the September CWCB meeting to hash out their concerns.

“The preliminary analysis that has been presented appears to expand historic use and creates potential injury,” Abby Ortega, general manager of infrastructure and resource planning at Colorado Springs Utilities told the CWCB at its May meeting.

Determining past use of the Shoshone water rights is important because it will help set a limit for future use. While changing the use of a water right is allowed by going through the water court process, enlarging it is not. The amount pulled from and returned to the river must stay the same as it historically has been.

As part of the River District’s deal to buy the water rights, the CWCB — which is the only entity in the state allowed to hold an instream flow water right — must officially accept the water right and then sign on as a co-applicant in the water court change case.

But Front Range water providers said that doing so would amount to an endorsement of the River District’s historical use estimate, which would mean taking a side in the Front Range versus Western Slope disagreement.

“If you agree to accept the right and as I understand it, the instream flow agreement, you’re agreeing to be a co-applicant, which risks you accepting their analysis,” said Alexandra Davis, an assistant general manager with Aurora Water, at the CWCB’s May meeting.

Some members of the Front Range Water Council have asked that the CWCB remain neutral during the water court change case. In May 9 and June 9 letters to the CWCB from Marshall Brown, general manager of Aurora Water, he said the CWCB shouldrefrain from endorsing any specific methodology or volume of water.

“… [T]he CWCB should remain neutral in the water court proceedings and defer to the court’s determination of the appropriate methodology and volumetric quantification,” the May 9 letter reads.

The River District’s offer does just that: It proposes that the CWCB should not take a position regarding the determination of historical use of the Shoshone water rights.

“We heard the issues that are most front and center from these entities,” Moyer said. “And so we are trying to find a path forward that works for everyone.”

But even if Front Range Water Council members are in favor of the proposal, it is unlikely to result in a cancellation of the hearing. CWCB Executive Director Lauren Ris said in an email that under the board’s rules, they are required to hold a hearing. And Jeff Stahla, public information officer at Northern Water, said they will still be asking for the hearing to proceed.

Spokespeople from Colorado Springs Utilities, Aurora Water and Denver Water all declined to comment on the River District’s proposal because it was marked as confidential.

Some members of the Front Range Water Council have concerns beyond CWCB neutrality that could be addressed at the September hearing.

In a May 14 letter to the CWCB, Denver Water’s CEO Alan Salazar said the water provider also wants to carry over some provisions from existing agreements like the Shoshone Outage Protocol. This agreement has an exception in cases of extreme drought that allows Denver Water to keep taking water if its reservoirs fall below certain levels and streamflows are low. Denver Water added that by omitting the last two decades of Shoshone water use, the River District’s study period is skewed, and that using an upstream stream gauge to measure historical use is improper.

The hearing is scheduled for the next CWCB board meeting Sept. 16-18. The board can approve or disapprove the acquisition of the water rights, or make changes to the proposal and adopt the amended proposal. The board is required to take action at the September hearing unless the River District approves an extension. Pre-hearing statements are due by Aug. 4.

CWCB board members Brad Wind, who is general manager of Northern Water, and Greg Johnson, manager of resource planning at Denver Water, recused themselves from the July 17 CWCB board meeting discussion of the Shoshone water rights and plan to recuse themselves from future Shoshone discussions and decisions.