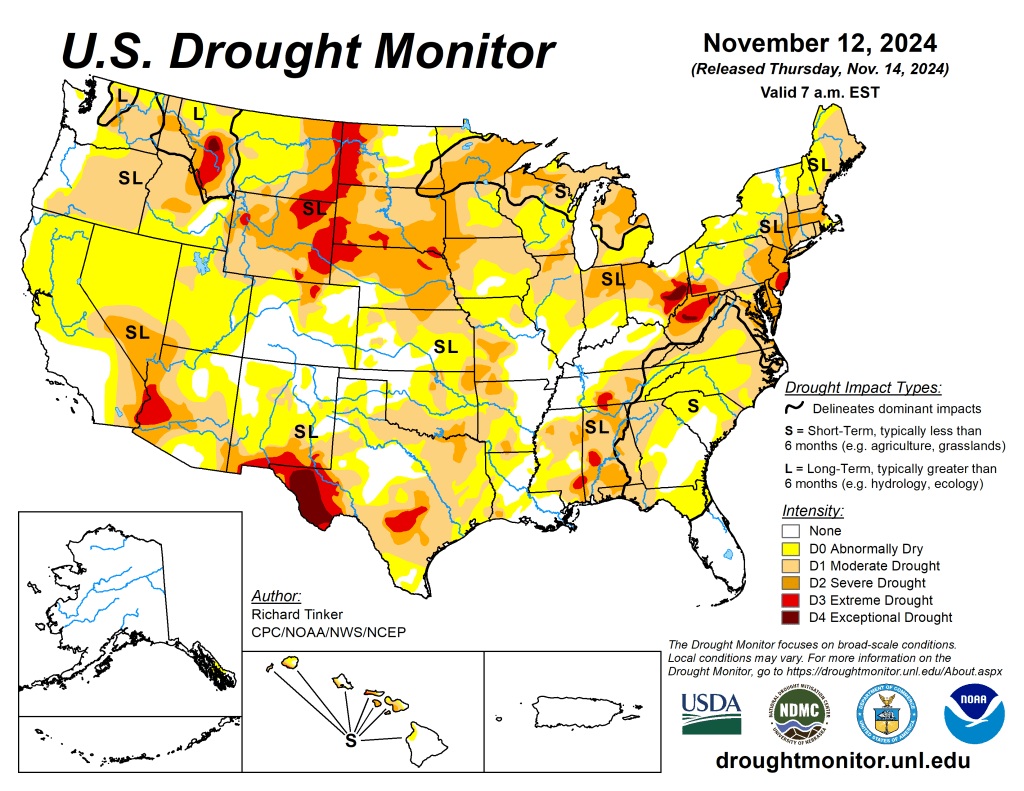

Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website:

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary

Storm systems brought significant precipitation and drought relief to broad areas in the central Rockies, central and southern Plains, Lower and Middle Mississippi Valley, Lower and Middle Ohio Valley, and the South Atlantic Region. Meanwhile, subnormal precipitation and some unseasonable warmth led to deterioration in dryness and drought conditions in portions of the Southwest, southern and western Texas, the interior Southeast, the northeastern Gulf Coast, the central and southern Appalachians, the mid-Atlantic region, the Northeast. Excessive precipitation totals fell on some areas. From central South Carolina through much of southeastern Georgia, amounts of 4 inches to locally a foot of rain were reported. Similar totals fell on central Louisiana, a band through central and north-central Texas, small parts of the Lower Ohio Valley, and orographically-favored areas in the Northwest. In addition, a broad area covering the eastern half of Colorado and adjacent areas in New Mexico and the central High Plains recorded 2 to 4 inches of precipitation, much of which fell as snow in the middle and higher elevations. A few scattered sites reported 3 to 4.5 feet of snow, mainly in the higher elevations of Colorado…

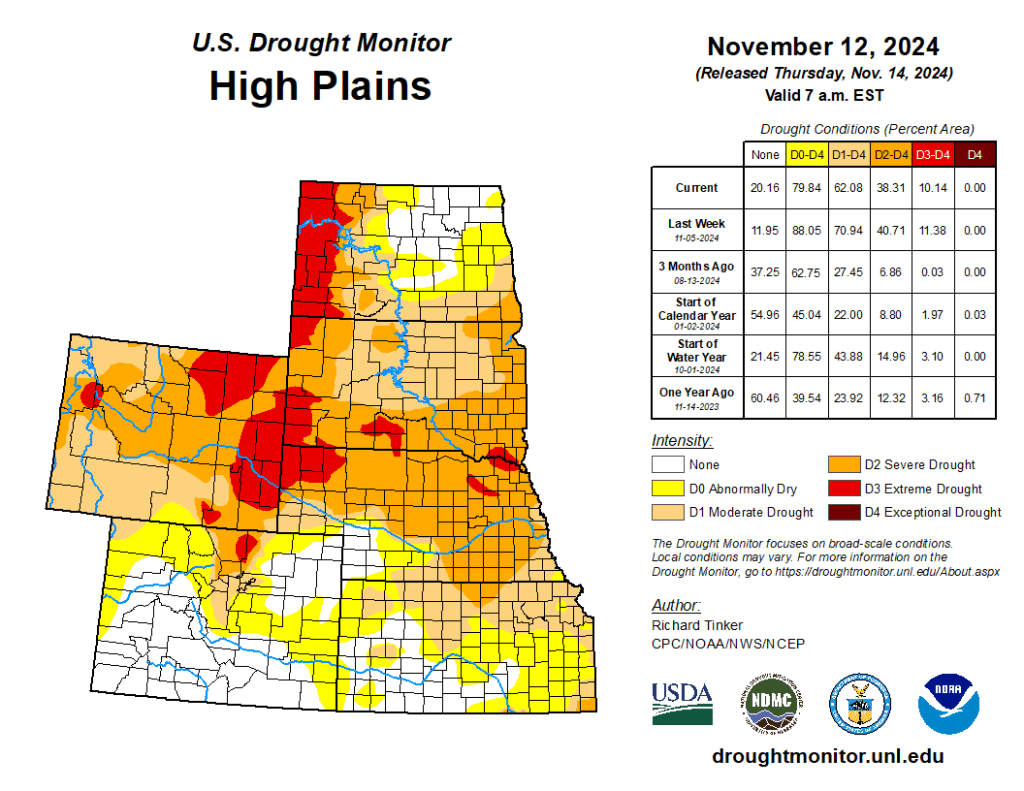

High Plains

A potent 500-hPa low triggered widespread heavy precipitation over southern half of the Region, except along the eastern fringe, while amounts were limited to several tenths of an inch at most farther north. Between 2 and 4 inches of precipitation fell on a large swath covering the eastern half of Colorado, most of central and western Kansas, and adjacent Nebraska. In nearby areas, amounts ranging from a few tenths of an inch to a couple of inches were observed over the western half of Colorado amounts of 0.5 inch to approaching 2 inches in spots was observed across southeastern Wyoming, most other areas in Nebraska, and eastern Kansas. Moderate amounts fell on a swath across the central and southwestern Dakotas the remainder of this region reported little or no precipitation, as well as most of Wyoming. In some of the higher elevations of Colorado, this precipitation fell as heavy snow, with a few locations reporting snow piling up 3 to 4.5 feet deep (50 to 54 inches buried Fort Garland CO while 44 to 47 inches were reported near La Veta, Elbert, and Trinidad CO). All of this resulted in a large area of improvement depicted over southern and western Kansas, most of northern and eastern Colorado, part of southwestern Nebraska, and a few spots in eastern Wyoming. There were a few areas of 2-class improvement in southeastern Colorado, northwestern Kansas, and the fringes of south-central and southeastern Kansas. Elsewhere, due to relatively cool weather, the dry week didn’t engender much deterioration, with most of these locations remaining unchanged from last week. One exception was in a small patch of northeastern Nebraska and adjacent South Dakota, where a new patch of extreme drought (D3) was identified…

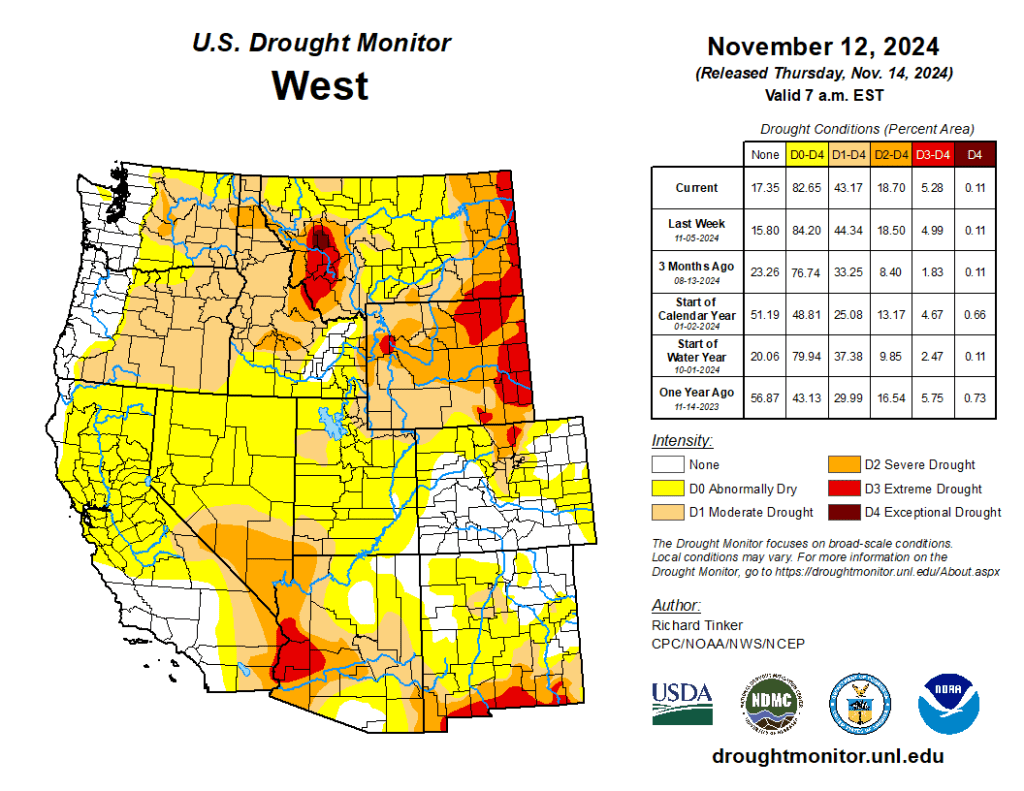

West

Heavy precipitation In northeastern New Mexico, with snow reported in some of the higher elevations, produced areas of improvement to dryness and drought. A few high spots in New Mexico reported near 3 feet of snow, including locations near Las Vegas NM and Folsom NM. The only other area of improvement in the West Region was in eastern Washington. Not much precipitation fell last week…

South

Like the Southeastern Region, the South Region experienced highly variable rainfall this past week. Heavy precipitation – in some areas for the second consecutive week – soaked a swath from Louisiana and eastern Texas northward through much of the Lower and Middle Mississippi Valley and the Tennessee Valley. A broad swath reaching as far west as central Arkansas recorded at least 1.5 inches in most places, with some areas recording much higher amounts (3 to 8 inches in part of western Tennessee, and over a foot in parts of central Louisiana). This resulted in reductions in dryness and drought severity across affected areas of the Lower Mississippi Valley and eastern Texas, with some 2-class improvements imposed in a small part of both southwestern Louisiana and an area straddling southwesternmost Mississippi and adjacent southeastern Louisiana. To the north, the heavy rains also removed abnormal dryness from across western Tennessee. Farther west, another area of heavy precipitation accompanied a frontal passage in a swath from central Texas into the central Red River (south) Valley, where totals reached 4 to 8 inches along the axis of heaviest amounts. To the north, heavy precipitation associated with a pair of potent upper-level low pressure systems dropped over 2 inches on a large part of central and western Oklahoma and much of the Texas Panhandle, with localized totals exceeding 4 inches in the eastern Texas Panhandle northward to the Oklahoma/Kansas border. There was also a patch of heavy rainfall to the east across portions of eastern Oklahoma, where isolated amounts peaked at around 3 inches. Dryness and drought affecting these areas were significantly eased, with a couple patches of 2-class improvements in north-central and northeastern Oklahoma. In stark contrast, little or no precipitation was observed from parts of southeastern Oklahoma southward through Deep South Texas, and across western Texas as well. Dryness and drought worsened in some of the areas, with the most widespread deterioration noted in western Texas. The broad area of exceptional drought (D4, the most intense category) expanded there to cover most or all of eastern Hudspeth, Culberson, western Reeves, Jeff Davis, Presidio, and Brewster Counties. Also, D3 (extreme drought) also expanded to cover most of the remainder of the Big Bend of Texas…

Looking Ahead

During the next five days (November 14-18), moderate to heavy precipitation is again expected from the Cascades westward to the Pacific Coast, with totals expected to exceed 5 inches expected in some of the higher elevations and orographically-favored sites. One or more inches are also anticipated in the Sierra Nevada, with several tenths of an inch possible along most of the California Coast down to the Mexican border. Parts of the northern Intermountain West are expected to receive over an inch of precipitation, with 2 to locally 4 inches forecast across the Idaho Panhandle. A low pressure system and trailing front should trigger another round of heavy precipitation in the central and southern Great Plains from central Texas northward into southeastern Nebraska and the Middle Mississippi Valley, with 1.5 to locally 4.0 inches anticipated from central and east-central Kansas southward through the Red River (south) Valley and adjacent northern Texas. At least an inch is also anticipated east of the Lower and Middle Mississippi River through the interior Southeast, Lower Ohio Valley, central and southern Appalachians, and the mid-Atlantic region. Over 2 inches may fall on parts of the central Appalachians and adjacent Piedmont. Meanwhile, moderate amounts should fall on the southern Rockies and adjacent High Plains and across the Great Lakes region and the northern Ohio Valley. In contrast, little or no precipitation is expected across much of the Northeast, Florida and the adjacent South Atlantic region, southern Texas, the northern Plains, the central and southern Rockies, and the Southwest.

The Climate Prediction Center’s 6-10 day outlook (valid November 19-23) features enhanced chances for both above-normal precipitation and temperatures across the Upper Midwest and across most areas east of the Mississippi River, with odds for significantly above-normal rainfall reaching 50 to near 70 percent on the Florida Peninsula. Wetter than normal weather is also slightly favored across Hawaii. Meanwhile, subnormal precipitation seems more likely across Texas and adjacent locations as well as the western Rockies, most of the Intermountain West, and the Sierra Nevada. Below normal temperatures are favored across the central and southern Plains and adjacent Mississippi Valley, the Rockies, and the Intermountain West. Southeastern Alaska should also average colder than normal while in Hawaii, neither extreme of temperature is favored.