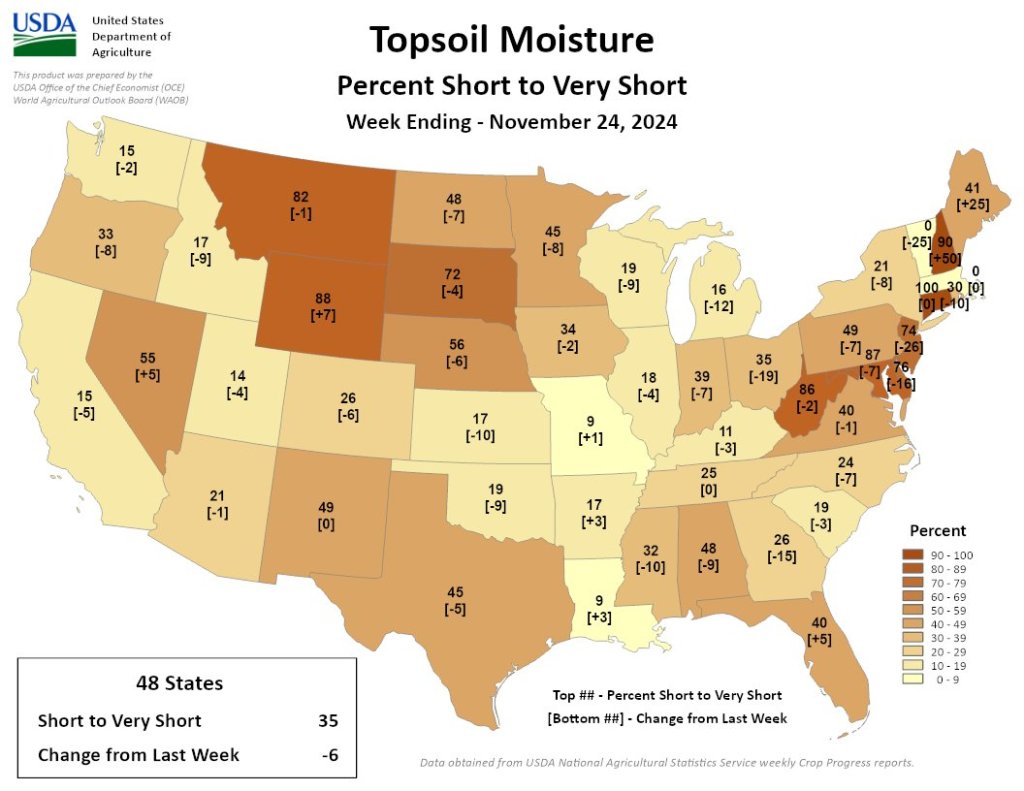

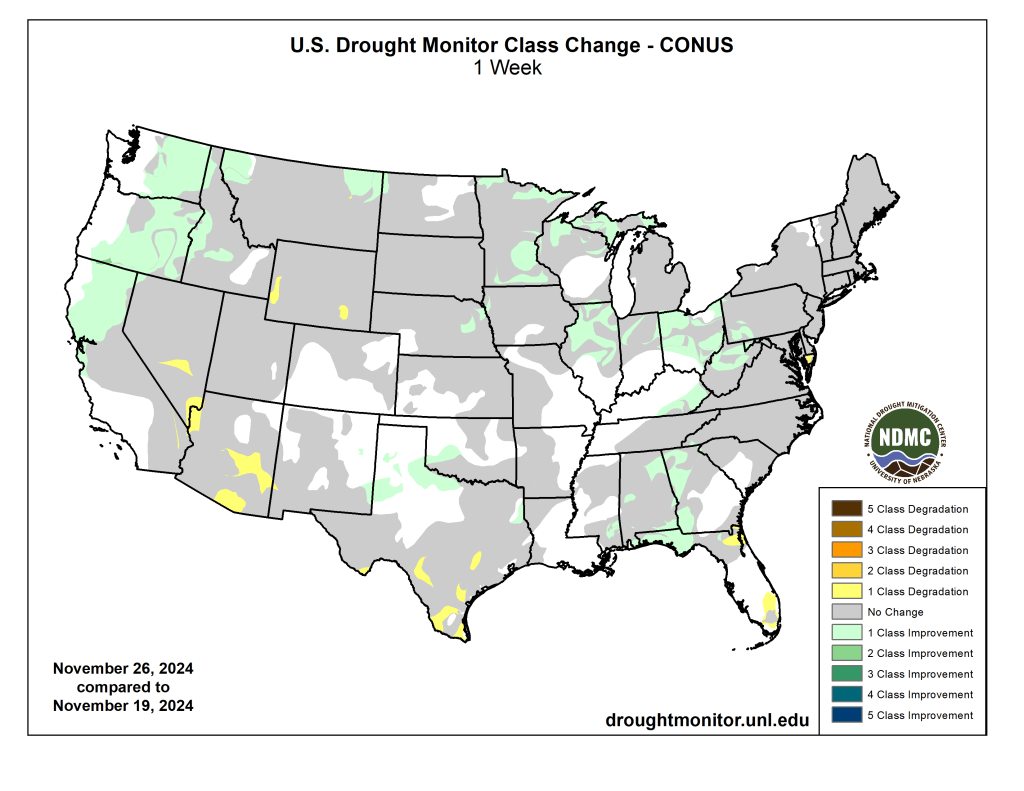

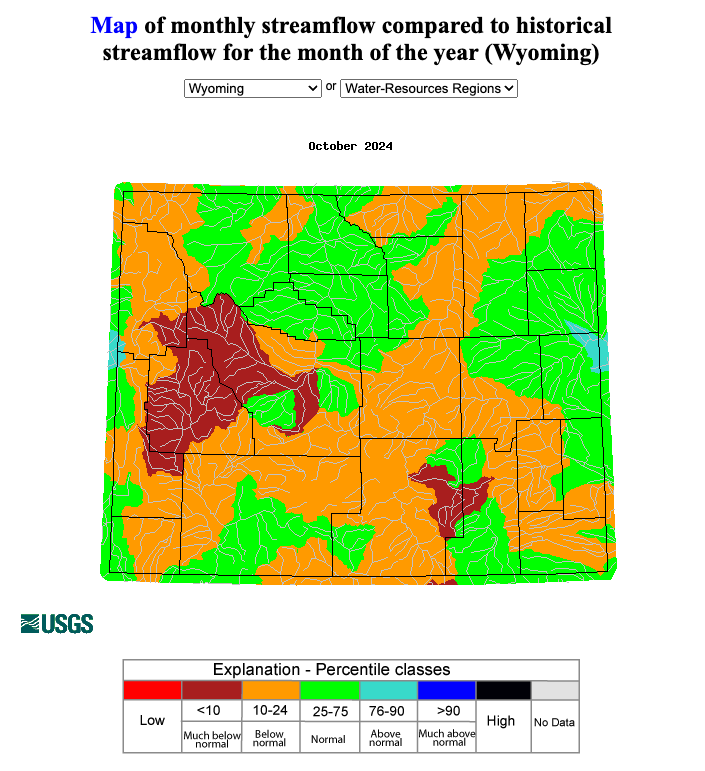

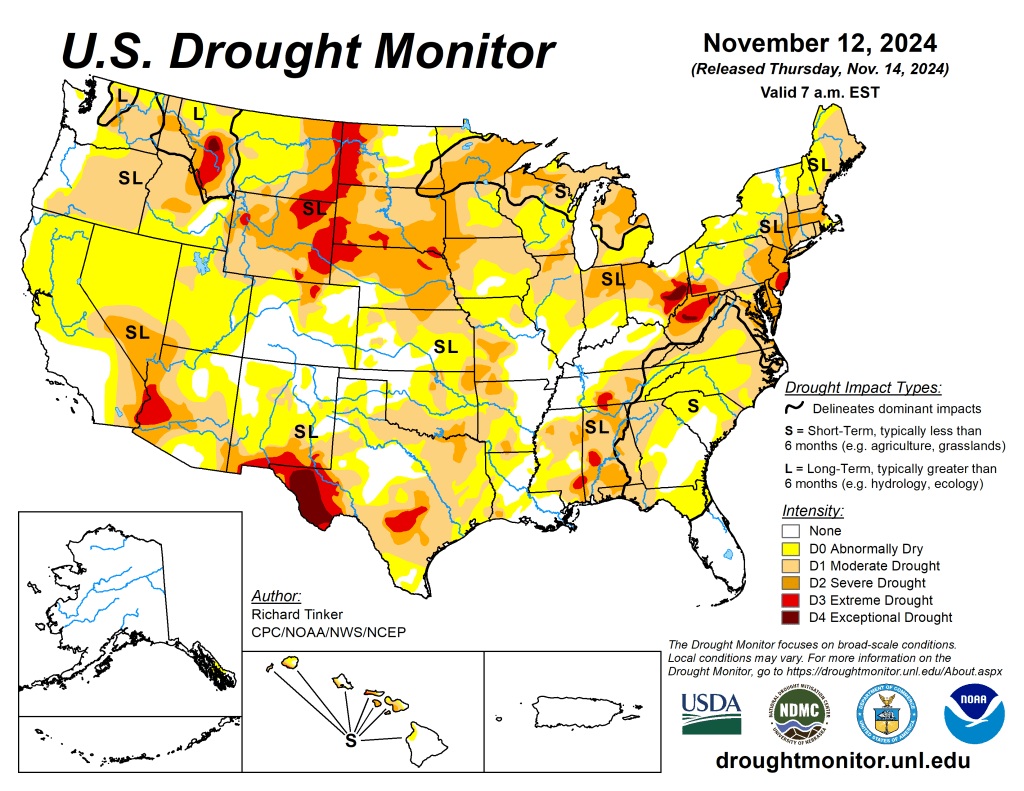

35% of the Lower 48 is short/very short, 6% less than last week. Soil moisture conditions improved in much of the U.S. this week. The exceptions? ME, NH, FL, AR, LA, WY, NV. Dry soils persist in the NE & Northern Rockies.

Month: November 2024

#Snowpack news: After winter storm surge, #Colorado snowpack levels may flatten amid week-long dry spell — Summit Daily

Click the link to read the article on the Summit Daily website (Robert Tann). Here’s an excerpt:

November 29, 2024

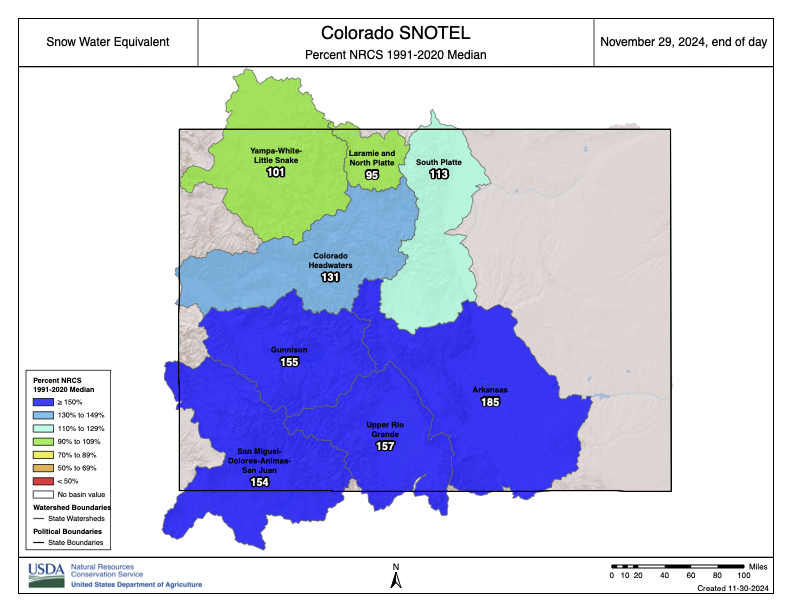

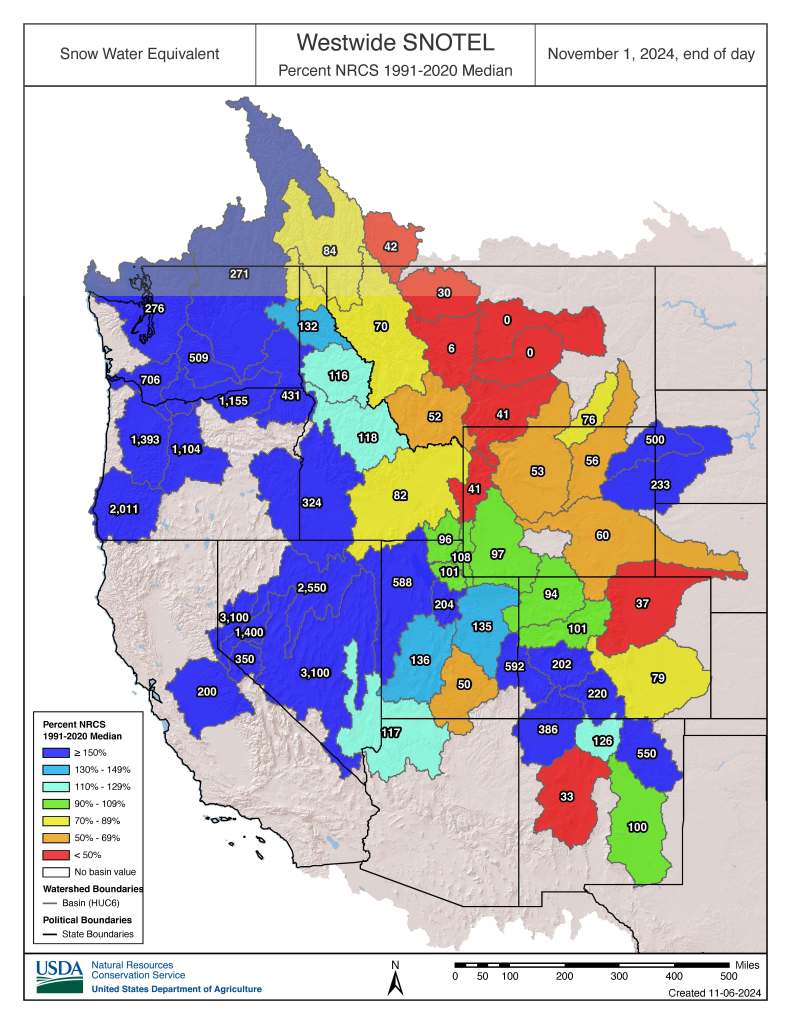

Snowpack levels in Colorado continue to outperform past years, with the latest surge driven by an intense series of winter storms that brought multiple feet of fresh snow across the High Country…Statewide snowpack levels reached 134% of the 30-year-median as of Friday, Nov. 29, according to data from the Natural Resources Conservation Service. It’s the highest level for this time of year in the past 10 years…River basins with the highest snowpack levels are concentrated in the southern half of the state, with snowpack in the Arkansas River Basin — which stretches from north of Colorado Springs to the New Mexico border — standing at nearly 200% of normal as of Friday. The central-mountain Colorado Headwaters River basin stood at 134% while the Yampa-White-Little Snake River Basin — which includes Steamboat Springs — stood at 103%. Snowpack levels typically peak in April, though the dates vary by basin…

Back-to-back storms late last week and through Wednesday have helped ski areas open acres of new terrain, with Copper Mountain becoming the first resort in Colorado to net 100 inches of snowfall this season.

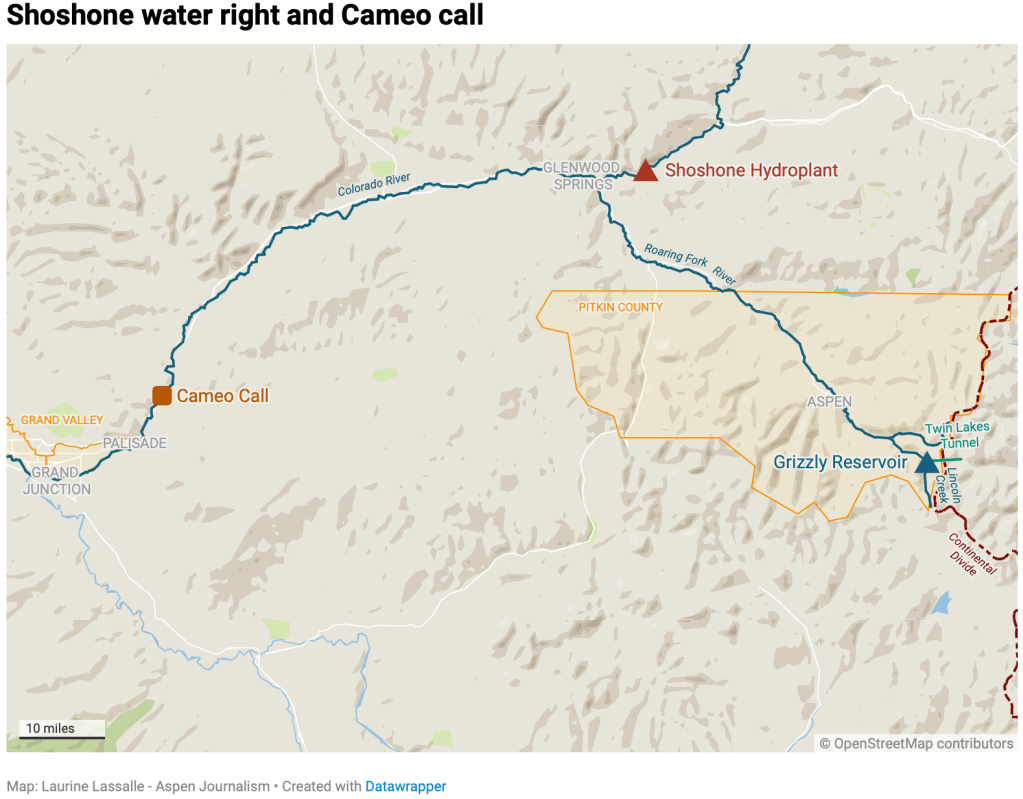

#ColoradoRiver District seeks federal funding to acquire Shoshone rights as Trump presidency brings uncertainty — Steamboat Pilot & Today #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the Steamboat Pilot & Today website (Ali Longwell). Here’s an excerpt:

November 29, 2024

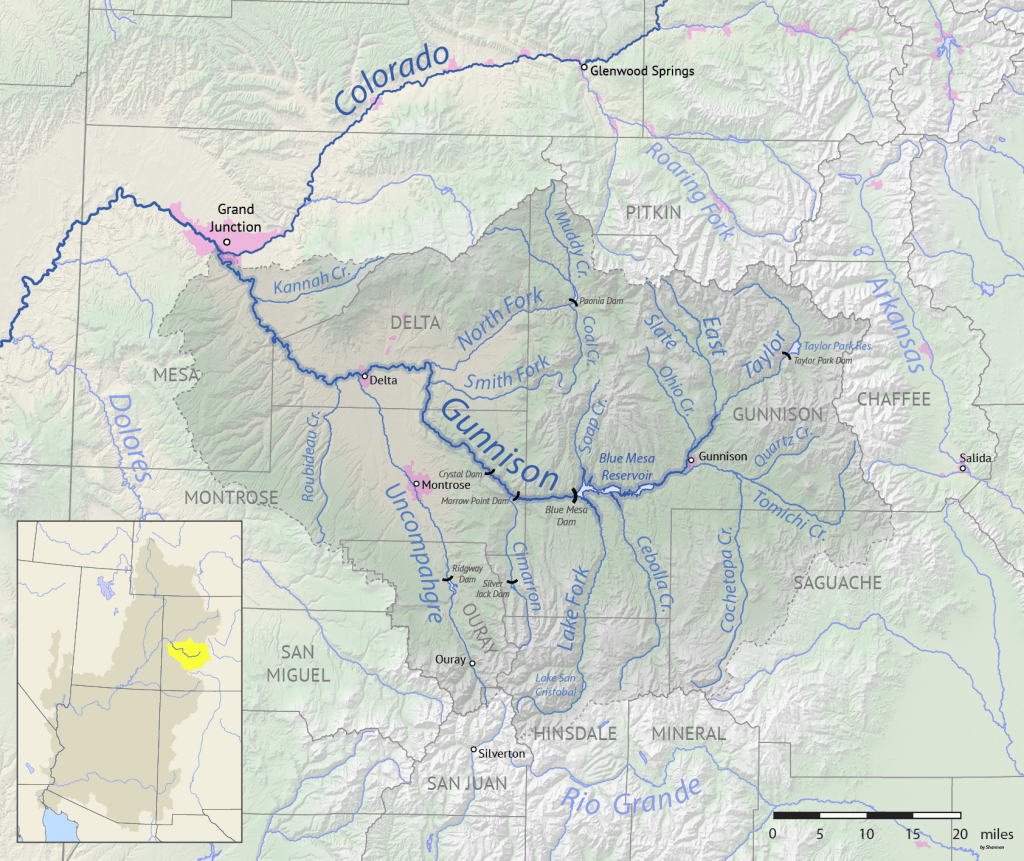

Last week, the governmental entity created to represent Western Slope water users submitted its 600-page application for $40 million from the Inflation Reduction Act, which allocated $4 billion toward drought mitigation efforts. The application falls under the Bureau of Reclamation’s Upper Colorado River Basin Environmental Drought Mitigation funding opportunity, also known as the Bucket 2E funding. The $40 million would go a long way toward the $98.5 million needed for the Colorado River District to purchase the water rights from Xcel Energy. So far, the district has raised around $56.9 million from the state legislature, its board and the various Western Slope municipalities and utilities it serves.

While the district’s request for federal dollars has received support from the majority of Colorado’s federal congressional delegation, the Inflation Reduction Act is likely to be targeted by Trump as he takes office in January. While the president-elect is unlikely to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act completely, he has promised to rescind any unspent funds under the act. The bureau is expected to award the Bucket 2E grants in the spring…Regardless of this uncertainty, Amy Moyer, the Colorado River District’s director of strategic partnerships, said the district “remains steadfast in its commitment to securing the Shoshone water rights and protecting the long-term health of the Colorado River.”

Romancing the River: Bluffing a Call, Calling the Bluff — George Sibley (SibleysRivers.com) #ColoradoRiver #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the Sibley’s Rivers website (George Sibley):

Breaking news! The Lower Colorado River Basin is threatening the Upper Basin with a ‘Compact Call’ if it does not agree to share some major cuts in river use! Well, actually the news broke a week ago – and now there’s more news: just as I was wrapping this analysis of the ‘Call’ up yesterday, the Bureau put out for our consideration five options for river management up to and beyond the 2026 termination of the ‘Interim Guidelines.’

So we’ll interrupt our out-of-the-box exploration for management options for living with a desert river in an intelligent universe, and try to figure out what’s going on back in the surreal world of the ‘Compact box’ – looking at the ‘Call’ situation here, then get into the five management options in a couple weeks after the dust has settled.

The Lower Colorado River Basin has attempted to break the stalemate between the two Compact-designated Colorado River Basins, by telling the Upper Basin that, if they do not agree to share some major cuts when the river situation grows desperate again, then in that desperate time they will issue a ‘Compact call’ on the Upper Basin to deliver the whole 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) on average they claim the Compact obligates the Upper Basin to deliver regardless of the water situation upriver.

There has been no formal Upper Basin Commission response to that threat, but Colorado’s Commissioner, and director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, Becky Mitchell, essentially called the bluff, and put the blame for Lower Basin problems back on the Lower Basin. The Upper Basin has argued that, if the situation becomes so desperate that the Lower Basin’ share cannot be delivered without draining Powell Reservoir, then the Upper Basin users will already be experiencing extreme shortages levied by nature.

This Hobson’s choice from the Lower Basin hinges on Article III(d) of the Colorado River Compact, which says, ‘The States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.’ Does this mean, as Lower Basin states will argue, that the Upper Basin has a ‘delivery obligation’ of 75 maf over any ten-year period, regardless what is happening weatherwise in the Upper Basin? Or does it mean, as Upper Basin states are likely to argue, should argue, that if the flow to the Lower Basin were to fall below that 75 maf over a ten-year period due to circumstances other than human uses in the Upper Basin states (drought, dead pool in Powell Reservoir due to excessive releases, the atmosphere’s growing ‘evaporative demand,’ et cetera), causing ‘the flow to be depleted’ below the 75 maf minimum, then responsibility for the depletion does not fall on the water users in the Upper Basin, but on changing natural processes beyond human control. The Upper Basin could, maybe should, argue that this condition in the Compact is simply a reminder to Upper Basin users, to be careful in using their 7.5 maf half of the river (cue bitter laughter), to not infringe on the Lower Basin’s 7.5 maf half of the river.

And so far as the Compact goes, that reminder is all there is. Nowhere in the Compact is there any provision for a ‘Compact call,’ or any other procedure when or if the flow at Lee Ferry (the ‘Mason-Dixon line’ between the two Basins) were to fall below that 75 maf over ten years. A ‘call,’ the reader might remember, is an unneighborly procedure in the appropriations doctrine that remains the foundation of water law in all seven Colorado River Basin states: if downstream water users with senior rights are not able to get all of their appropriated water, they can place a ‘call’ on upstream users with junior rights, who have a legal obligation to let enough water go past their headgates to fill the seniors’ rights.

A seven-way division of the use of the river, however, proved to be nearly impossible. Each commissioner had come with the charge to protect their own state’s glorious future, to develop their vast acreage of potentially irrigable land, their mineral resources, et cetera. No factual studies existed to support the glorious visions. And when the water requirements for those visions were all added up, they would have required a river half again larger than even the overly optimistic flow numbers provided by the Bureau of Reclamation.

The Bureau hovered around the Compact meetings, eager to ‘make concrete’ the final purpose stated in that Compact preamble: ‘to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property from floods.’ The Bureau wanted to build big dams on the Colorado River, and ‘expeditious agricultural and industrial development’ was the rational cloak the Bureau and the commissioners could throw on over the romantic urge to just take on the conquest of Fred Dellenbaugh’s ‘veritable dragon’ of a river.

Herbert Hoover, U.S. Secretary of Commerce and chair of the Compact Commission, and an engineer by training and romantic inclination, also wanted to build big dams. And when the commissioners grew frustrated at their failure to resolve an equitable seven-way split of the use of the river after several days of looking at magical numbers, he worked hard to keep them from just dropping the whole idea, reminding them that Congress would not approve funding for Colorado River projects until the seven states all felt satisfied that a share of the river would be there for them when they were ready to grow like California.

Still, he was unable to pull them together for a serious working meeting until November, nearly the end of the year they had given themselves to create their interstate compact. He was able to lure them with an idea he and Delph Carpenter, Colorado’s commissioner, had cooked up over the summer: instead of the currently impossible seven-way division based on vague visions, they would work out a two-way division, dividing the river into two Basins, the four tributary states mostly above the river’s canyon region as an Upper Basin, and the three states mostly below the canyons as a Lower Basin, and each Basin could have the use of half the river, to divide further among each Basin’s states at their leisure.

Holed up at the posh Bishops’ Lodge just north of Santa Fe, with 28 formal meetings in 11 days and who knows how many off-the-record breakfast and bar caucuses and drafting sessions, they came up with a Compact that no one loved, but six of the seven thought they could live with, to satisfy Congress that they were all on the same page.

The seventh state was Arizona. Arizona’s commissioner, W.S. Norviel saw from the start that this two-basin idea caged the thousand-pound gorilla, California, to the satisfaction of the four Upper States, but left his state in the cage with the gorilla. He signed off on the Compact – possibly so Hoover would let them go home – but his state legislature refused to ratify the Compact. And all the other six states only ratified it after months of persuasion that it was as good as they were going to get.

Congress, on the other hand, was sufficiently infected with the romance of conquest to be willing to ratify the Compact with only six of the seven states on board. The next step was the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1928, clearing the way for the construction, begun under President Hoover, of Hoover Dam, Parker Dam, the Imperial Weir Dam and the All-American Canal – a massive project that was about the only thing happening in America in the Great Depression, and which was adopted by the Roosevelt administration as the model for the Public Works Program and several other New Deal programs to put America back to work on big visions.

But at the base of all that is the rushed and rickety Colorado River Compact, the ricketiness of which was acknowledged by most of the commissioners – and by Hoover himself, who in one of the later November compact meetings, summarized the emerging compact as ‘a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river.’ (Italics added) If the legal and political infrastructure isn’t quite in place – never mind: go ahead and build the physical structure anyway.

We have the whole chain of laws, subsequent compacts, court decisions, interim guidelines and other fixes that have tried to shore up the Compact – the Law of the River – but nothing that really addresses the matter of the 7.5 maf promise to both basins that the river cannot support – and that the Lower Basin now seems to be considering, on the basis of that Article III(d) obfuscation, as an appropriated right that the gives them a kind of seniority over the Upper Basin.

Isn’t that what this ‘Compact Call’ threat is? Hasn’t the Lower Basin essentially tried to graft the Compact onto the appropriations doctrine in order to threaten the Upper Basin with a ‘Compact call,’ despite the expressed intent of the Compact to create an equitable division that would preclude post-Compact appropriation calls between states?

I’ll leave it there, hoping that someone with a greater fund of information can explain this to me. Watch the ‘Comments’ section here.

And then we’ll dig into the Bureau’s recommendations in a week or two. And forget, for the time being, trying to think outside the Compact box; it demands our attention, love it or not.

Public lands are an asset — Pete Kolbenschlag (Colorado Farm & Food Alliance @ColoFarmFood)

From email from Pete Kolbenschlag:

The West’s public lands are an iconic and a cherished asset that belong to all Americans. They are also deeply rooted in the practicality of place, in the agricultural and hardscrabble ways of the West’s rural towns and far-flung communities. Public lands have been established over decades, and are still enduring now, as a public asset.

Public lands are an especially American legacy, founded in an anti-nobility tradition as an investment in the nation and in our shared future. These lands are part of the character and history of those who live here, and few would easily give them up. Still, there is also another legacy that continues to this day that runs contrary to all that. Privatizing the public domain has been on the to-do list of robber-barons and others for over 100 years.

Public lands provide ecological services, like ensuring a good water supply, making our businesses, farms, communities and lives here possible. But few would say that the management of public lands has not been fraught with problems, resources often neglected, policy captured by industries and interests it is meant to regulate.

Too often those with a narrow and self-interested agenda hide behind the well-founded misgivings people have about how public lands are managed. Most recently it is the State of Utah as stalking horse, advancing a court challenge that seeks to undermine the very foundations of America’s public lands. According to an alert from Backcountry Hunters & Anglers: “The catch is simply this: the transfer of public lands from federal to state governments is the pathway to streamlined privatization. Despite the State’s adamant claims that it intends to “keep public lands in public hands,” the reality of the matter is that the bar for sale is significantly lower under State control than it is under the current federal management system, which has proven to be very effective at retaining lands in the public domain.”

Westerners who have been around awhile can often see these plays to take the public’s lands for what they are. Often wearing the familiar look of the rural West and pulling on a populist appeal, these ploys serve a specific and narrow set of interests. Many seasoned observers are not surprised to see these same deep-pocketed interests at it again, seeking to turn public lands to their own purposes.

At the start of the 20th Century many large livestock operations, absentee speculators, and fly-by-night operators intent on exploiting the West’s resources wanted the public’s lands turned over to their purposes and to benefit their needs. And those with this agenda have made significant progress at various times, so we know what is at risk. We also know which interests stand to gain the most from taking America’s public assets away: it’s not the public.

This time it’s dressed up in a novel legal argument engineered for the Supreme Court, which is a reason for real concern. But it’s not a new agenda. The motivations and monied-interests behind it are as old as the American West itself. When I first arrived in the West it was the “Wise Use Movement,” which was itself just the Sagebrush Rebellion repackaged. And while the agenda is not novel, the threat this time is significant. Many point to a Supreme Court that has recently favored corporate over community interests. Undemocratic forces that seek to monetize public resources for private gain have strong allies in powerful positions.

Public land agencies evolved from the needs of a growing nation and from on-going conflicts. National Forests were reserved, in the case of the North Fork Valley, to protect downstream- from upstream-agriculture because the headwaters were being poorly managed and overgrazed by sheepherders, impacting fruitgrowers in Paonia. Western range wars were also a thing at the turn of the previous century, and western Colorado saw its share. Public lands management began, in part, to ensure a more equal footing for use of the public’s shared parks, open spaces, and wildlife lands.

The Bureau of Land Management grew out of the grazing service, general land office and other Interior Department agencies. The land office had been administering the Homestead and similar acts, and when the “frontier was closed,” federal lands – which had been seized, secured and opened up with federal treasure (provided mostly by eastern taxpayers) – became a public asset to be managed for broader benefit. Grazing reform, mineral leasing laws, and other rudimentary land management practices were established to protect resources that the public relied on.

Elections matter and America has again chosen its leaders. Now our water, natural resources, and the right to have a liveable climate could all be in the balance, again. Luckily an antidote to the misappropriation of public wealth is also part of the western body politic. In western Colorado we will have a new Congressman and our national public lands will be managed with a different agenda.

Make sure that your government’s representatives and agencies, along with your family and friends, businesses you shop at and customers you serve, all know how important public lands are to you. These places are at the core of the West. Be ready to act. Speak up for your public lands now.

Pete Kolbenschlag is a long-time public lands activist and currently the director of the Colorado Farm & Food Alliance based in Paonia, Colorado.

Draining #LakePowell Won’t Solve Crisis — the Associated Press

Click the link to read the article on the Associated Press website (Tom Howarth). Here’s an excerpt:

As the American Southwest grapples with a historic water crisis, some advocacy groups, such as the Glen Canyon Institute (GCI), propose drastic measures like draining Lake Powell to address the diminishing flow of the Colorado River. However, Arizona’s top water official, Tom Buschatzke, has warned that this approach could exacerbate the problem rather than resolve it. Buschatzke, the director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, outlined the risks of removing Lake Powell from the equation in the broader water management system. His argument underscores the importance of maintaining the reservoir as a buffer against the volatility of the Colorado River’s flow.

“Bigger reductions in the flow of the river that might attend to climate change are something that is being looked at,” Buschatzke told Newsweek. “But if you take Lake Powell out of the equation, the yield of the system is going to go down.”

[…]

“There will be wet years in which you won’t have storage to save the water,” he said. “So the overall yield over a longer-term average has to go down without Lake Powell. That means you have less usable water, and that might not be the outcome you’re trying to achieve.”

[…]

The proposal to drain Lake Powell also highlights a broader philosophical divide in water management: incremental fixes versus transformative changes. According to Buschatzke, large-scale reforms, while potentially impactful, are fraught with challenges…Groups like the GCI disagree with Buschatzke, arguing that bypassing Glen Canyon and adopting a “Fill Mead First” policy could not only help manage water in the system more effectively but also recreate the landscape lost when Glen Canyon Dam was first constructed in the 1960s. As the levels of the lake have receded in recent years, plants and animals have reclaimed in the shores in what’s been dubbed an “ecological rebirth.”

Happy Thanksgiving!

#Drought news November 28, 2024: The NRCS SNOTEL network is reporting (November 25) the following region-level (2-digit HUC) SWE levels: #MissouriRiver 78%, Upper #ColoradoRiver 96%, Lower Colorado 127%, #RioGrande 145%

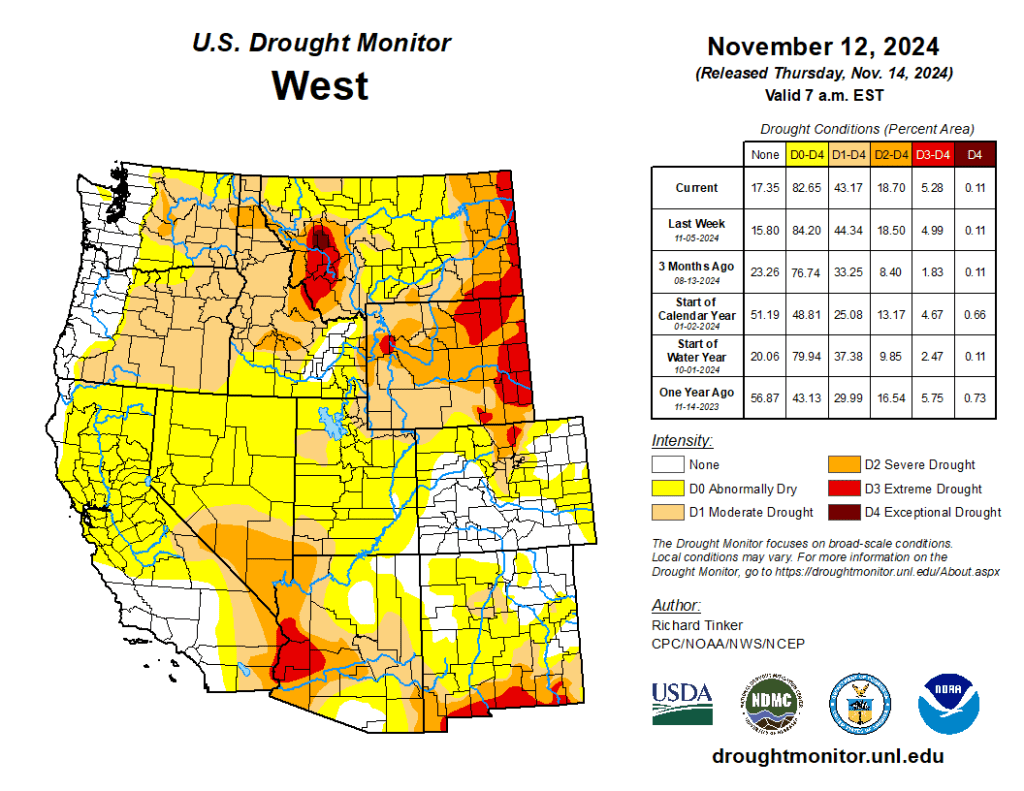

Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click on the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

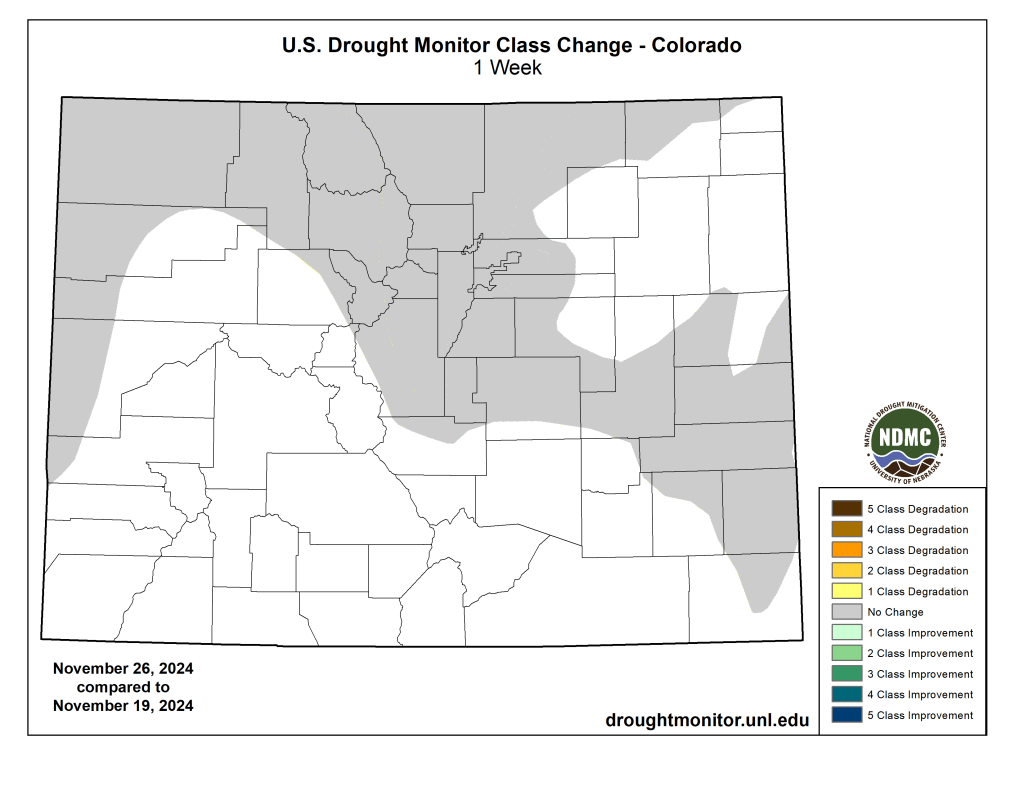

This Week’s Drought Summary

This U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) week saw widespread improvement in drought-related conditions across areas of the Pacific Northwest and Northern California in response to a series of strong Pacific storms including a powerful atmospheric river that delivered significant rainfall accumulations to the lower elevation coastal areas and heavy mountain snow. In the coast ranges of Northern California, 7-day rainfall totals exceeded 25+ inches in some areas, according to preliminary data from the National Weather Service (NWS) California-Nevada River Forecast Center. The series of storms boosted mountain snowpacks above normal levels across the Cascades (Oregon, Washington), Blue Mountains (Oregon), Sawtooth Range (Idaho), and the northern and central Sierra. In the Desert Southwest, drought expanded and intensified on the map across areas of southern Nevada and Arizona in response to persistent dry conditions and record warm temperatures during the past 6-month period. In the Midwest, improving short-term conditions due to recent precipitation events across areas of the region led to widespread improvements in drought-affected areas. In the Northeast, light-to-moderate precipitation accumulations, including beneficial snowfall, led to a reduction of areas of drought coverage in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. In the Southeast, rainfall last week and overall improving conditions (soil moisture, streamflows) led to the removal of areas of drought on the map in Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.

In terms of reservoir storage in areas of the West, California’s reservoirs continue to be at or above historical averages for the date (November 25) with the state’s two largest reservoirs (Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville) at 111% and 105% of their averages, respectively. In the Southwest, Lake Powell is currently 37% full (59% of typical storage level for the date) and Lake Mead is 32% full (53% of average), with the total Lower Colorado system 42% full as of November 18 (compared to 43% full at the same time last year), according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. In Arizona, the Salt River Project is reporting the Salt River system reservoirs 75% full, the Verde River system 57% full, and the total reservoir system 73% full (compared to 81% full a year ago). In New Mexico, the state’s largest reservoir along the Rio Grande is currently 7% full (17% of average). In the Pacific Northwest, Washington’s Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake is 90% full (103% of average for the date), Idaho’s American Falls Reservoir on the Snake River is 35% full (86% of average), and Hungry Horse Reservoir in northwestern Montana is 82% full (100% of average)…

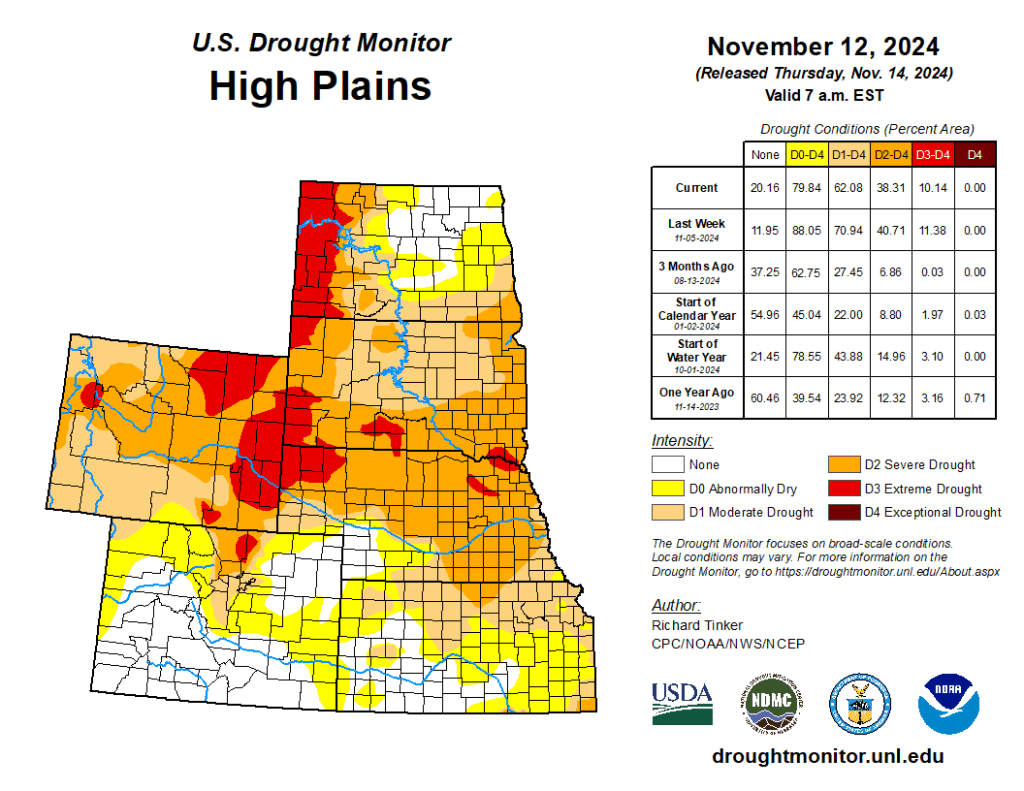

High Plains

On this week’s map, only minor changes were made in the region including in eastern Nebraska and western North Dakota. For the week, precipitation across the region was generally light and primarily restricted to eastern portions of the Dakotas and Nebraska as well as western and northern portions of Kansas. However, some isolated moderate-to-heavy snowfall accumulations were observed in the Dakotas last week, including 14 inches reported at Lake Metigoshe State Park in northern North Dakota. In terms of average temperatures, cooler-than-normal temperatures (3 to 9 deg F below normal) were observed across the Dakotas, while the southern portion of the region experienced temperatures 1 to 5 deg F above normal in eastern Nebraska and Kansas…

West

Out West, a series of powerful Pacific storms delivered heavy rain and mountain snow accumulations to the Pacific Northwest and Northern California. Impacts from the series of storms included damaging winds, major power outages, flash flooding, road closures, landslides, and debris flows. In the Coastal Range, an NWS observing station northwest of Santa Rosa, California reported a 7-day total of 24 inches of rain. Overall, the series of storms led to widespread removal of areas of drought on the map across the Pacific Northwest as well as areas experiencing short-term dryness across Northern California. Looking at the regional snowpack situation, the NRCS SNOTEL network is reporting (November 25) the following region-level (2-digit HUC) SWE levels: Pacific Northwest 179%, Missouri 78%, Upper Colorado 96%, Great Basin 125%, Lower Colorado 127%, Rio Grande 145%, Missouri 78%, Souris-Red-Rainy 128%, and Arkansas-White-Red 157%. In the Desert Southwest, areas of Extreme Drought (D3) expanded on the map this week in northwestern Arizona, extending northward into southern Nevada, in response to a combination of short and long-term precipitation deficits and record heat observed during the past 6-month period. Elsewhere in the region, the atmospheric river last week boosted snowpack conditions in Montana, helping to improve drought-affected areas in the northwestern part of the state…

South

Across the region, generally dry conditions prevailed this week, especially in the western portion of the region, with little or no precipitation observed across the western half of Texas and Oklahoma. However, light to moderate rainfall (2 to 4+ inches) was observed in isolated areas of southern Louisiana and Mississippi leading to minor improvements in drought-affected areas of southeastern Mississippi. For the week, average temperatures were near normal across the southern extent of the region while northern portions ranged from 3 to 6 degrees F above normal. On the map, deterioration occurred in isolated areas of Texas including the Trans Pecos, South Texas, and the southern Edwards Plateau, while improvements were made in the Panhandle and east Texas. Looking at reservoir conditions in Texas, Water for Texas (November 26) was reporting statewide reservoirs at 72% full, with many reservoirs in the eastern part of the state in good condition, while numerous reservoirs in the western portion of the state were experiencing continued below-normal levels…

Looking Ahead

The NWS Weather Prediction Center (WPC) 7-Day Quantitative Precipitation Forecast (QPF) calls for light-to-moderate precipitation accumulations ranging from 1 to 2 inches (liquid) across areas of the Intermountain West including the Colorado Rockies and ranges in central and southern Utah. Lighter accumulations are expected in the southern Sierra, North Cascades, and areas of the northern Rockies. Along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, light accumulations (<1 inch) are forecasted for the 7-day period. In the Upper Midwest and areas downwind of the Great Lakes in the Northeast, accumulations of <1 inch are expected. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) 6-10-day Outlook calls for a moderate-to-high probability of above-normal temperatures across the West and near-normal temperatures across the Plains states. Conversely, below-normal temperatures are expected across the Eastern tier. In terms of precipitation, there is a low-to-moderate probability of above-normal precipitation across much of Texas and Louisiana as well as areas of the northern Plains. Elsewhere, below-normal precipitation is expected across much of the West, Central and Southern Plains, Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and New England.

Tools for better environmental adaptation as we manage the #ColoradoRiver — John Fleck (InkStain.net) #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the InkStain website (John Fleck):

November 15, 2024

I put up a slide for my University of New Mexico water resources graduate students during class yesterday afternoon with two pictures – the emerging canyons at the upper end of Lake Powell, and a smallmouth bass.

When Lake Powell gets low, we get a) the remarkable emergence of Cataract Canyon, and b) warm water invasive smallmouth bass sneaking through Glen Canyon Dam’s outlets, headed downstream to dine on the endangered humpback chub. My University of New Mexico colleagues and collaborators Benjamin Jones and Bob Berrens famously dubbed these “green-vs-green” tradeoffs:

Managing for one – keeping Lake Powell high to keep smallmouth bass out of the Grand Canyon – inevitably conflicts with the other – keeping Lake Powell low to protect the emerging environmental values of Cataract Canyon.

In a new white paper out today, my colleagues Jack Schmidt, Eric Kuhn, and I argue for the creation of a process to better incorporate and manage the multiplicity of values along the Cataract Canyon/Lake Powell/Glen Canyon/Grand Canyon/Lake Mead stretch of the Colorado River as we develop new post-2026 river operating guidelines. We recognize that keeping water flowing to taps and headgates across the Colorado River Basin is the primary motivation behind the new operating guidelines being developed by the Bureau of Reclamation. We argue that, as the community is writing those rules, we have an opportunity to incorporate a broader set of community values.

In particular, we argue that more creative water accounting methods would allow water to be either held upstream in Lake Powell for later delivery, or send downstream early to Lake Mead, in order to better take into account what Benjamin and Bob called the “multiple dimensions of societal value.”

The white paper elaborates on our formal proposal submitted in March to Reclamation as part of the agency’s Post-2026 decision process.

Road trip do-over: Not an excellent EV adventure so far

So when I got to the Hertz rental office yesterday they did not have a Polestar as I had reserved so the clerk said they would substitute similar vehicle, a Suburu Solterra. I thought, “Okay, that might be a nice ride.”

I motored east on I-70 thinking that I would do a first charge in Limon where I had charged my Leaf before because it showed up on a map from an app recommended by Hertz. When I arrived at the charging location the chargers were all offline. When I checked the ChargePoint app later the location didn’t show up which tells me that it has been closed.

It was a bummer but I had enough charge to get Flagler where I had also charged my Leaf there once before. When I connected I was immediately stunned by the charger telling me that it would take more than two hours to 100%. This can’t be right I thought, the charger (Electrify America) is capable of providing 350 KW of shared charge. I called Hertz and was told that the Solterra does not charge at Level 3. The only cars they have that charge at Level 3 are Teslas and Polestars.

I charged enough to get back home (3% charge when I arrived), hooked up to my Level 2 charger for an hour or so, then returned the car.

While charging at Flagler I called Avis to rent a Tesla. I picked up the car (Model 3) this morning and it crapped out just before Central Park Avenue on I-70. After being towed back to Avis I now have a different Tesla (Model Y) and am heading out again.

Coyote Gulch outage

Despite Biden Administration Proposals to Address #ColoradoRiver Shortages, a Solution Is Far Off — Inside #Climate News #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the Inside Climate News website (Wyatt Myskow):

November 21, 2024

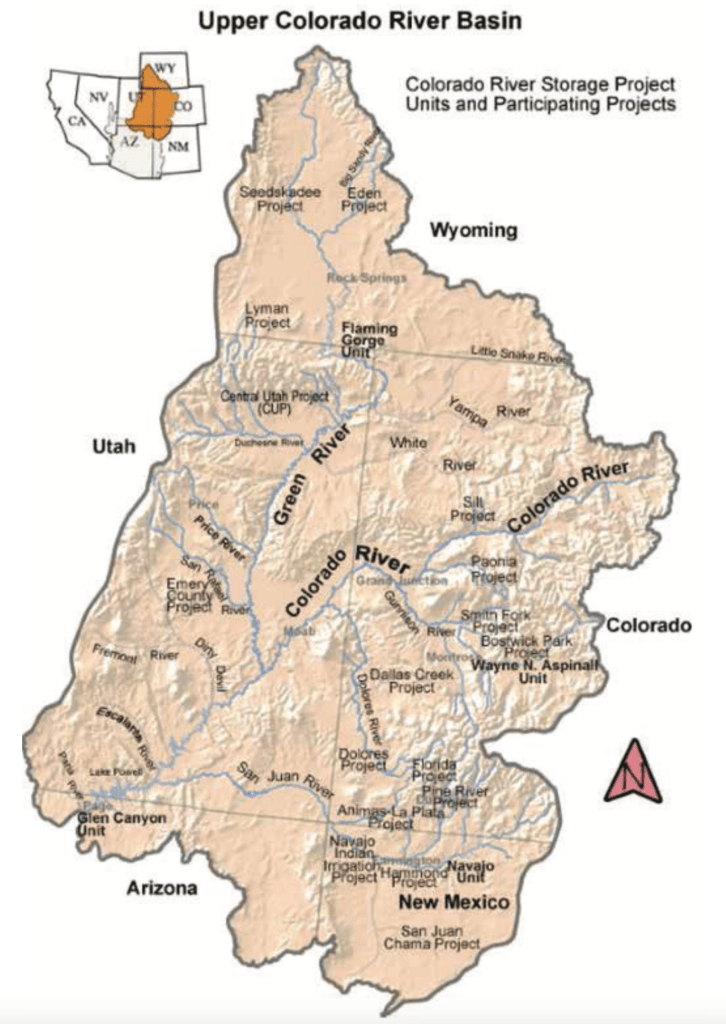

The Biden administration on Wednesday released four alternatives to address the drought-stricken Colorado River’s water shortages, giving seven states, 30 tribes and the 40 million people who rely on the river a taste of how the vital waterway will be managed in the coming decades.

But the announcement offers little in the way of hard details, with a draft environmental impact statement analyzing the impacts of the Department of Interior’s proposed alternatives pushed back to next year. The states, meanwhile, remain divided over the path forward to deal with shortages on the river. Over the past year, the seven Colorado River Basin states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming—along with tribes and the federal governments have been in negotiations over the “Post-2026 Operations” for the river that will dictate how to deal with water shortages. The river’s current drought guidelines, drafted in 2007, will expire at the end of 2026.

“We continue to support and encourage all partners as they work toward another consensus agreement that will both protect the long-term stability of the Colorado River Basin and meet the needs of all communities,” said Laura Daniel-Davis, the acting deputy secretary of the Department of Interior. “The alternatives we have put forth today establish a robust and fair framework for a Basin-wide agreement. As this process moves forward, the Biden-Harris administration has laid the foundation to ensure that these future guidelines and strategies can withstand any uncertainty ahead, and ultimately provide greater stability to the 40 million water users and the public throughout the Colorado River Basin.”

The river that enabled the Southwest’s rapid growth and vital agricultural production has seen its flows diminished roughly 20 percent over the past two decades by a megadrought. Climate change and years of overuse of the river’s resources have led the system’s massive reservoirs—lakes Mead and Powell—to fall to just a third of their capacities. That prompted steep cuts in allocations of the river’s water to Arizona, California and Nevada, and tense negotiations over its future. Further declines at the reservoirs could cause their respective dams to reach minimum power pool, where they can no longer generate electricity, or dead pool, when the water drops too low to flow through the concrete dams’ plumbing.

The Colorado River Basin is regulatorily split in two. The Upper Basin consists of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. The Lower Basin is composed of Arizona, California and Nevada, which historically has used more of the river. Under the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divided up the river’s resources and is the bedrock document for how it is governed, the Upper Basin is required to allow the Lower Basin states’ allocation of water to flow downstream before it can use its half of the river. If the Upper Basin fails to send the required amount of water, its own allocation could be cut.

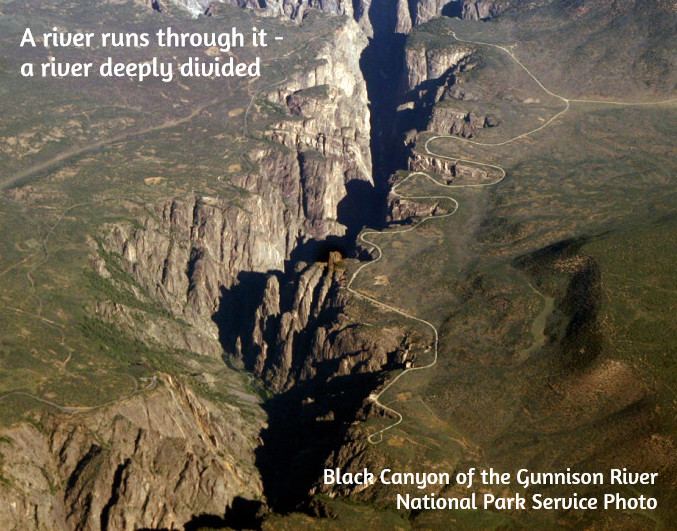

Earlier this year, each basin submitted its own proposals for how it would manage the river’s water post-2026, but there was little agreement between their plans. The Upper Basin argued that, since it does not have large reservoirs and its users already have to make cuts anytime there is drought, it should be able to send less water downstream and the Lower Basin should bear responsibility for cutbacks. Under the Lower Basin’s proposal, all users would be forced to take cuts based on the total amount of water held in eight reservoirs across the entire system. Meanwhile, tribes have submitted their own proposals and comments, as have environmental groups.

The two basins remain deeply split, and though both sides are committed to coming to an agreement, it’s possible that the question of how Colorado River water will be divided and distributed between the basins will have to be settled in court, KUNC reported earlier this week. The Upper Basin representatives also maintain it has the right to take more water out of the river, given it does not use its full share, something that’s drawn the ire of its lower basin counterparts, environmental groups and water attorneys.

The Interior Department will analyze the four options presented Wednesday in an environmental assessment, with a final decision planned for 2026 on how to advance the process the Biden administration began and that President-elect Donald Trump’s administration will have to take over. One alternative is the federal government’s plan to “achieve robust protection of critical infrastructure,” like Hoover and Glen Canyon dams and the large amounts of hydropower they produce, along the river. Another combines that plan with comments from tribes and others. A third follows a proposal submitted by environmental groups, while the fourth combines the proposals of the states and tribes.

“Big picture: There’s still a lot of conflict about how Lake Powell will be managed,” said Kyle Roerink, the executive director of the Great Basin Water Network. A key difference between the alternatives is how water would be released from Lake Powell, the massive reservoir in the middle of the river system. He said the Upper Basin’s proposal would use it as a “piggy bank” to store water for them while the Lower Basin, which has priority rights to the water, wants to see it used to deliver what it is owed by the upstream states.

The states themselves say it will take time to fully analyze the proposals put forth by the Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees the river’s management, but neither side seems excited about the options, though they’ve admitted the need to continue working together.

“There are some really positive elements to these alternatives, but at the same time I am disappointed that Reclamation chose to create alternatives, rather than to model the Lower Basin states’ alternative in its entirety,” said Tom Buschatzke, the director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, in a statement. “The Lower Basin’s alternative didn’t start at one extreme or the other, and it showed unequivocally that the Lower Basin was willing to take the first tranche of cuts.”

In a statement, Colorado River Commissioner Becky Mitchell said that “Colorado continues to stand firmly behind the Upper Division States’ Alternative, which performs best according to Reclamation’s own modeling and directly meets the purpose and need of this federal action.

“The Upper Division States Alternative is supply-driven and is designed to help rebuild storage at our nation’s two largest reservoirs,” she said. “The Alternative protects Lake Powell’s continued ability to release water downstream into the future to continue to meet our obligations and protect our significant rights and interests in the Colorado River.”

Roerink likened the Biden administration’s efforts to bring water users together as “herding cats” and said that Wednesday’s decision may help bring them back to the table to find a solution. But the divide between the two basins remains wide. “Change is scary,” he said.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News (hyperlink to the original story), a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Audubon’s Jennifer Pitt Testifies before Congress on #ColoradoRiver Habitats: Audubon supports bills that support wildlife habitat amid changing #climate #COriver #aridificationd

Click the link to read the release on the Audubon website (Jennifer Pitt):

November 20, 2024

The following is the oral testimony of Jennifer Pitt, Audubon’s Colorado River Program Director before a House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife and Fisheries:

Chair Bentz, Ranking Member Huffman, and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for holding this hearing on proposed legislation addressing water management in the western United States. My name is Jennifer Pitt and I serve as the Colorado River Program Director for the National Audubon Society, with over 25 years of experience working on water issues in the Colorado River Basin. National Audubon Society is a leading national nonprofit organization representing more than 1.4 million members and supporters. Since 1905, we have been dedicated to the conservation of birds and the places they need, today and tomorrow, throughout the Americas using science, advocacy, education, and on-the-ground conservation. Audubon advocates for solutions in the Colorado River Basin that ensure adequate water supply for people and the environment.

Audubon supports H.R. 9515, the Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program Amendment Act of 2024. The Program constructs habitats along the Colorado River below Hoover Dam, and that habitat is essential not only for the 27 species the program targets, but also for many of the 400 species of birds that rely on the Lower Colorado River, including Yellow-billed Cuckoos, Sandhill Cranes, and Yuma Ridgway’s Rails. Today, because the Program spending does not keep pace with the collection of funds from non-federal partners, about $70 million is held in non-interest-bearing accounts. If these funds were held in an interest-bearing account, the Program would have about $2 million in additional funds per year, and be more able to maintain program implementation in the face of increasing costs.

Audubon appreciates the inclusion of H.R. 9969 in this hearing. This bill directs Reclamation and the Western Area Power Administration, in consultation with the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Work Group, to enter into a memorandum of understanding to explore and address potential impacts of management and experimental actions to help control invasive fish passage in the face of drought and declining water levels. Rapidly changing conditions on the Colorado River warrant the experimental approach of adaptive management, with the Work Group bringing together varied interests to a consensus on how to protect downstream resources and strike a balance on river operations. Results of this collaboration include improved sediment flows that help maintain sandy beaches used by plants and animals that dwell in the floodplain, as well as by people traveling the canyon by boat.

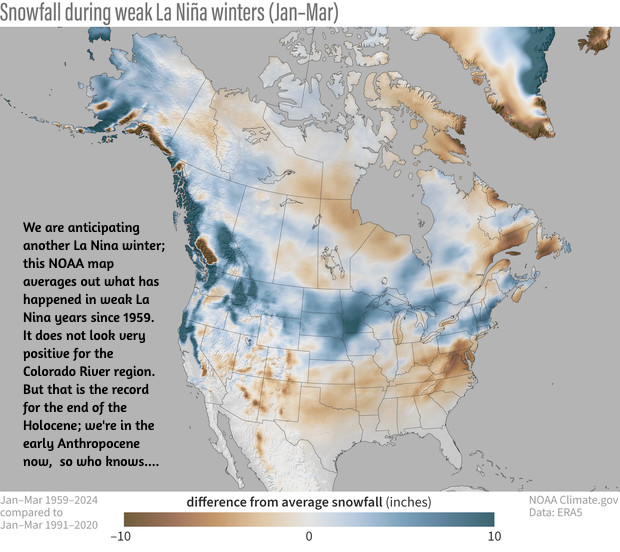

The context for these bills is the current crisis on the Colorado River. Climate change continues to ravage the Colorado River Basin, which is now in its 25th year of drought. The forecast for this winter is for above-normal temperatures and below-normal snowpack, which could impact Colorado River water supply. With a 2026 deadline looming for the expiration of existing federal guidelines for operation of federal Colorado River infrastructure – with implications for water supply reliability for people and the river itself – human nature is creating unacceptable risks. Colorado River water managers are preparing for conflict to protect their share of an increasingly scarce water supply, rather than focusing on holistic solutions.

Earlier this year, Audubon joined with conservation partners in submitting to Reclamation our Cooperative Conservation Alternative for consideration in the post-2026 NEPA process for developing Colorado River Operating Guidelines. Cooperative Conservation is designed to improve water supply reliability, reduce the risk of catastrophic shortages to farmers and cities, create new flexible tools that can protect infrastructure, incentivize water conservation, help Tribes realize greater benefits from their water rights, and improve river health. We urge Reclamation and all Colorado River Basin parties to consider our approach as they proceed through the NEPA process.

From a bird’s eye view, the whole system matters. That needs to hold true for water users who must figure out how to share the Colorado River. The old adage applies: united we stand, divided we fall. The Colorado River community – in particular Upper Basin and Lower Basin interests – must stop thinking parochially and start thinking about how we survive drier times together.

I would like to thank Congress for funding water conservation programs, such as WaterSMART and the Cooperative Watershed Management Program, and the crucial funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, both of which include funding to improve the resilience of the Colorado River Basin. With this funding, and states working together, we have avoided a crisis, but we are still just one bad winter away from catastrophic shortages. To be effective, this funding needs to get out of federal coffers and into the hands of water users and water managers, to incentivize water conservation and efficiency, to improve the health of the forests and headwater streams that are the river’s source, and to stabilize the river itself – the natural infrastructure that supplies water to more than 40 million people. Congress will need to help in the future with additional funding to support continued resilience investments in the Colorado River Basin as warming continues.

Thank you very much for the opportunity to testify and I would be happy to answer your questions.

Public land protectors are ready for a fight — Jennifer Rokala (WritersOnTheRange.org)

Click the link to read the article on the Writers on the Range website (Jennifer Rokala):

November 18, 2024

President Donald Trump’s first term was a disaster for America’s public lands. While the prospects for his second term are even more bleak, Westerners across the political spectrum—even those who voted for Trump—stand ready to oppose attempts to sell off America’s public lands to the highest bidder.

As for Trump’s pick for Interior Secretary, North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum: If Burgum tries to turn America’s public lands into an even bigger cash cow for the oil and gas industry, or tries to shrink America’s parks and national monuments, he’ll quickly discover he’s on the wrong side of history.

Public lands have strong bipartisan support in the West. The annual Conservation in the West Poll, last released by the Colorado College State of the Rockies Project in February 2024, found that nearly three-quarters of voters—including Republicans—want to protect clean water, air quality and wildlife habitats, while providing opportunities to visit and recreate on public lands.

That’s compared to just one-quarter of voters who prefer maximizing the use of public lands available for drilling and mining. According to the poll, which surveyed voters in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—80 % of Westerners support the national goal of conserving 30 % of land and waters in America by the year 2030.

Bipartisan support for more conservation and balanced energy development has been a cornerstone of the poll’s findings since it began in 2011. Under the leadership of President Joe Biden and Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the current administration has made progress over the past four years in bringing public land management in line with the preferences of Western voters. That includes better protecting the Grand Canyon, increasing accountability for oil and gas companies that operate on public land, and putting conservation—at last—on par with drilling and mining on public land.

The President-elect may find it hard to immediately block what Westerners want. After Trump took office in 2017 promising to transform public land management, his team was unprepared and used its power to benefit its own interests, ignoring the wishes of the American people.

Trump’s first Interior secretary, Ryan Zinke, misused his position to advance his dream of owning a microbrewery in Montana. Trump’s second Interior secretary, oil and gas industry lobbyist David Bernhardt, put his finger on the scale in the interest of a former client. Trump’s choice to run the Bureau of Land Management, William Perry Pendley, served illegally without being confirmed by Congress.

We worked hard to shed light on this corruption and defend public lands from Trump’s attacks. Still, Trump’s Interior department allowed oil and gas companies to lock up millions of acres for bargain basement prices.

In his second term, Donald Trump will attempt to shrink national monuments like Bears Ears in Utah and permit drilling and mining in inappropriate areas. The president-elect has already committed to undoing President Joe Biden’s energy and environmental policies.

Project 2025, the policy handbook written by former Trump officials, clearly lays out a plan to gut the Interior Department and remove environmental safeguards that ensure the health of our public lands.

Project 2025 would give extractive industries nearly unfettered access to public lands, severely restrict the power of the Endangered Species Act, open millions of acres of Alaska wilderness to drilling, mining and logging and roll back protections for spectacular landscapes like Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments. It would also remove protections for iconic Western species such as gray wolves and grizzly bears.

What can we do about this assault? The law and public opinion are on our side. Public land protections are stronger today than ever, thanks in large part to the grassroots efforts of Tribes, local community leaders and conservation organizations.

We know much of what’s in Trump’s public lands playbook, and we will fight back. We’ll continue to shine a light on corruption within the Trump administration and hold it accountable.

Our partners will work in Congress to stop bad policies and projects from going forward. We are ready to take action in the courts and in the streets. And we’re not waiting until Inauguration Day to start.

Jennifer Rokala is a contributor to Writers on the Range, writersontherange.org, an independent nonprofit dedicated to spurring lively conversation about Western issues. She is executive director of Center for Western Priorities, a nonpartisan public lands advocacy group.

The Western Slope just asked for federal #climate dollars to buy crucial water rights — #Colorado Public Radio #ColoradoRiver #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the Colorado Public Radio website (Ishan Thakore). Here’s an excerpt:

November 22, 2024

A $99 million plan to buy and permanently preserve some of the oldest water rights in Colorado is inching closer to securing all of its funding. But President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to gut climate spending could throw a wrench in the deal, despite its bipartisan support. The Colorado River District, which advocates on behalf of Western Slope water users, submitted a funding application today to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation under a program for drought mitigation. The district is seeking $40 million from the federal agency to help purchase water rights from Xcel Energy, the state’s largest utility…

Since the agreement, around 25 Western Slope water providers, the river district and the state of Colorado have committed $56 million to purchase the water rights. The state’s water conservation board, much of Colorado’s congressional delegation, and a bipartisan group of state lawmakers support the plan. To make up the remaining funds, the river district is banking on money from the Inflation Reduction Act, the nation’s largest climate law, which was signed by Biden in 2022. Bureau of Reclamation records show the agency has $450 million remaining under the law to dole out to state, local and tribal governments in the upper Colorado River Basin for projects that offset the effects of drought and climate change…

That stream of federal funding for the Shoshone water deal has not yet been committed and could be in jeopardy, according to Martin Lockman, a law fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. President-elect Trump said he would rescind any remaining funds from the inflation law when he returns to office. Project 2025, a conservative policy blueprint influential among the president-elect’s advisors, has called for repealing elements of the law.

Briefs: Colorado River plans, Snowpack status: Bureau of Reclamation teases a #ColoradoRiver plan, leaves us thirsty for more — Jonathan P. Thompson (LandDesk.org) #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

November 22, 2024

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

The Bureau of Reclamation released a sort of teaser of its eagerly anticipated plan for dealing with the demand-supply imbalance on the Colorado River. And like most teasers, it gives very little insight into what to expect from the actual plan. It presents four alternative ways forward, but doesn’t say which one the agency is leaning towards. But they all are at least partially aimed at keeping Lake Powell’s surface level above the minimum power pool, so that water can continue to be released via the penstocks and hydroelectric turbines. This would put most of the burden for cuts on the Lower Basin states, which could experience up to a 3.5-million-acre-feet shortage some years. This doesn’t cut it for John Weisheit, Living Rivers’ Conservation Director, who noted:

But there may be even less water than previously anticipated in the Colorado River in the future, throwing even the best laid plans askew. That’s the finding of a recent study, in which researchers ran historic data and climate change forecasts through modeling programs, yielding hundreds of thousands of streamflow scenarios for the Colorado River and its tributaries originating on Colorado’s West Slope. They concluded that relying on the historic streamflow record risks underestimating the magnitude of future drought events. And these droughts could significantly reduce the amount of water flowing in Colorado River tributaries, throwing supply and demand further off balance.

Patrick Reed, the study’s principal author, said in a press release:

And if less water is going into Lake Powell, then its operators will release even less water from Glen Canyon Dam, meaning deeper shortages for the millions of folks downstream who rely on the river.

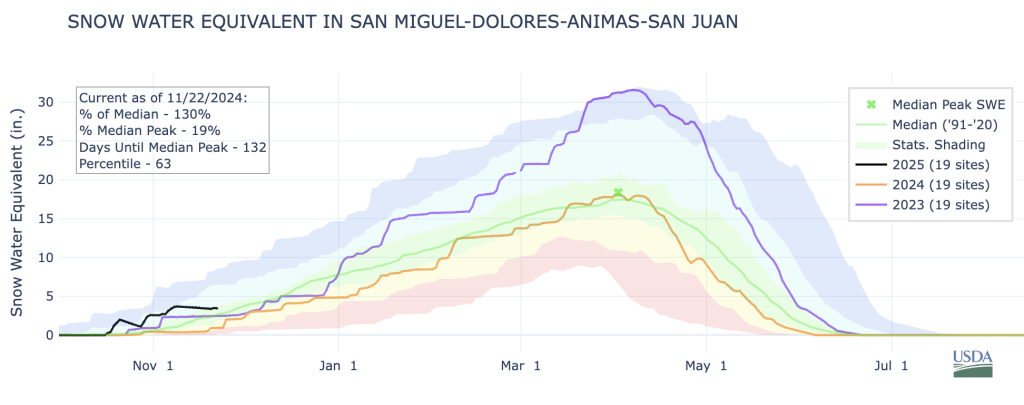

For now, however, things are looking alright for the Colorado River. Some good autumn storms built up the snowpack, which is now sitting right at about the median level for this time of year in the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Meanwhile, things are quite nice, snowpack-wise, down in the San Juan Mountains, where snow-water levels are higher than this date’s normal and significantly healthier than at this time in 2024 or 2023. And another storm is on its way.

Will the good times last? According to the latest seasonal climate outlook, probably not. Forecasters are expecting it to be drier and warmer than normal in the Southwest, though things could go either way in the northern portion of the Colorado River Basin. But then, it’s always best to take these long-term forecasts with a hefty grain of salt.

🏠 Random Real Estate Room 🤑

Where can you get, in 2024, 1.36 acres that includes an old post office, a 104-year-old cabin, a converted bus, and at least one RV for just $75,000? Cisco, Utah, that’s where. The property was immortalized by Sarah Gilman in her 2018 High Country News article “The Pioneer of Ruin,” a profile of the owner and Cisco’s sole resident Eileen Muza. Miranda Trimmier also wrote about Cisco and Muza for Places Journal in 2019, and a variety of other media attention followed about their effort to restore that piece of the “ghost town.” The property was listed in July for $275,000 — Muza’s partner apparently was not interested in living out there — but the price was dropped to $75,000 this month. It’s certainly one of the funkier properties on the market and probably the least expensive housing for sale in the greater Four Corners area. But the “housing” part isn’t official: Even though Muza lived there and it sports several dwellings, the property is listed as land, not a residence (so it won’t show up on searches for houses). But you’d better move quick if you’re interested: It showed up on the 2.9-million-follower @cheapoldhouses Instagram feed recently, so it could go fast. Heck, at that price, I even briefly considered it for the Land Desk/Lost Souls Press global HQ!

And just down the road, in that illustrious Cisco suburb known as Moab, about 100 people gathered to protest the proposed Kane Creek Development. The developers want to build nearly 600 housing units and associated infrastructure at a place called Kings Bottom on the banks of the Colorado River a couple miles downstream from Moab. It’s not going over so well with many locals. That’s just a crap ton of houses, it would all be vulnerable to flooding (meaning a good portion of the homes, and the contents of a planned sewage treatment plant, could end up floating in Lake Powell someday). I suppose the developers could move the whole operation up to Cisco.

In an alternate reality, in which the Bureau of Reclamation circa 1946 had its way, Cisco might be waterfront property right now. For more on that, check out this piece from the Land Desk archives (available to paid subscribers only):

Cisco Resort and other water buffalo oddities — Jonathan P. Thompson

June 1, 2022

Gratuitous Silver Bullet Shot

Mrs. Gulch’s landscape November 22, 2024

The latest Seasonal Outlooks through February 28, 2025 are hot off the presses from the #Climate Prediction Center

Reclamation announces $3.3M in WaterSMART Small-Scale Water Efficiency grants for 36 projects: The funding is used along with $3.8 million in local and state funding to support water efficiency projects in 10 states

Click the link to read the release on the Reclamation website:

November 21, 2024

The Bureau of Reclamation has selected 36 projects to receive a total of $3.3 million in federal funding to enhance water efficiency across the Western United States. The funding, provided through the Small-Scale Water Efficiency Projects program, will support initiatives such as the installation of flow measurement or automation systems, canal lining to reduce seepage, and other similar projects that aim to improve water management on a smaller scale.

“As stewards of vital water resources, it is our responsibility to ensure that every drop is used efficiently,” said Bureau of Reclamation Chief Engineer David Raff. “These investments, while focused on smaller-scale projects, have a lasting impact on our ability to conserve water, protect ecosystems, and support the communities that depend on these critical resources.”

The Bureau of Reclamation is now accepting applications for the next Small-Scale Water Efficiency Projects program funding opportunity, with a deadline of January 14, 2025.

For more information on how to apply for funding, visit grants.gov. To learn more about the program and find details about projects in your area, visit the program’s website.

The projects selected are:

Arizona:

- Coldwater Canyon Water Company, Upgrade Manual Read Meters to Advanced Meter Reading Technology: Reclamation Funding: $91,786

- Global Water Resources, Turf Removal Incentive Program for Residential and Non-Residential Customers: Reclamation Funding: $50,000

- Joshua Valley Utility Company, Phase III: Upgrade 400 Meters to Advanced Reading Technology: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Sonora Environmental Research Institute, Inc, High-Efficiency Clothes Washer Replacement Program for Low-Income Households: Reclamation Funding: $47,500

California:

- City of Hercules, Enhancing Park Irrigation Efficiency with Cloud-Based Controllers: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Cucamonga Valley Water District, Water Savvy Parkway Transformation Program: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Desert Water Agency, Grass Removal Program: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Fresno Irrigation District, Meter Installation Program: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Jackson Valley Irrigation District, Propeller Meter Upgrades: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency, Remote Data Acquisition for High Production Groundwater Wells: Reclamation Funding: $97,878

- San Lorenzo Valley Water District, AMI Water Meter Replacement Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Upper San Gabriel Valley Municipal Water District, Water Use Efficiency Plant Voucher Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

Colorado:

- Community Agriculture Alliance Inc, Automate Headgates on the Bear River: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Town of Fraser, 2026 Water Meter Modernization and Replacement Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Town of Simla, Municipal Water Meter Upgrade for Water Efficiency: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

Idaho:

- A&B Irrigation District, Water Accounting Software Implementation and Project Upgrade: Reclamation Funding: $47,500

- Boise Project Board of Control, Automation of the Brooks Lateral: Reclamation Funding: $24,967

- Fremont Madison Irrigation District, Fremont-Madison Irrigation District Automation and SCADA Project Phase 4: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Jefferson Irrigation Company, Flow Measurement of Irrigation Canal Turnouts for Jefferson Irrigation Company, LTD: Reclamation Funding: $99,715

- Long Island Irrigation Company, Main Diversion Replacement: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Upper Wood River Water Users Association, Inc, Bypass Canal Lining Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

North Dakota:

- Agassiz Water Users District, Agassiz Water Users District 2024 Remote Read Water Meter Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- City of Bottineau, City of Bottineau, Advanced Metering Infrastructure Project – Phase I: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- City of Mandan, Mandan Advanced Metering Infrastructure System Update Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- City of Watford City, Watford City Advanced Metering Infrastructure Project – Phase II: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Southeast Water Users District, Southeast Water Users District: Advanced Metering Infrastructure Improvements Phase II Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

Nevada:

- City of Boulder City, Boulder City Water Meter Upgrades: Reclamation Funding: $98,613

Oregon:

- Colton Water District, Automated Meter Reading: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Ochoco Irrigation District, Inc, J1 Lateral Pipe and Metering Project: Reclamation Funding: $36,574

South Dakota:

- Belle Fourche Irrigation District, Anderson Lateral Pipeline: Reclamation Funding: $83,406

Utah:

- Circleville Irrigation Company, Dalton Ditch Water Conservation Project – Phase 3: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Clinton City, Clinton City AMI Project Phase I: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Draper Irrigation Company, Culinary Smart-Metering Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Jensen Water Improvement District, Residential Meter Replacement and Upgrade Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

- Powder Mountain Water and Sewer Improvement District, System-Wide Radio Read Meter Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

Washington:

- Clallam County PUD No. 1, Small-Scale Advanced Metering Infrastructure Project: Reclamation Funding: $100,000

Reclamation provides cost share funding the Small-Scale Water Efficiency Projects to irrigation and water districts, Tribes, states and other entities with water or power delivery authority for small water efficiency improvements, prioritizing projects that have been identified through previous planning efforts.

Small-Scale Water Efficiency Projects are part of the WaterSMART Program. It aims to improve water conservation and sustainability, helping water resource managers make sound decisions about water use. The WaterSMART Program identifies strategies to ensure this generation, and future ones, will have enough clean water for drinking, economic activities, recreation and ecosystem health. To learn more, please visit www.usbr.gov/watersmart.

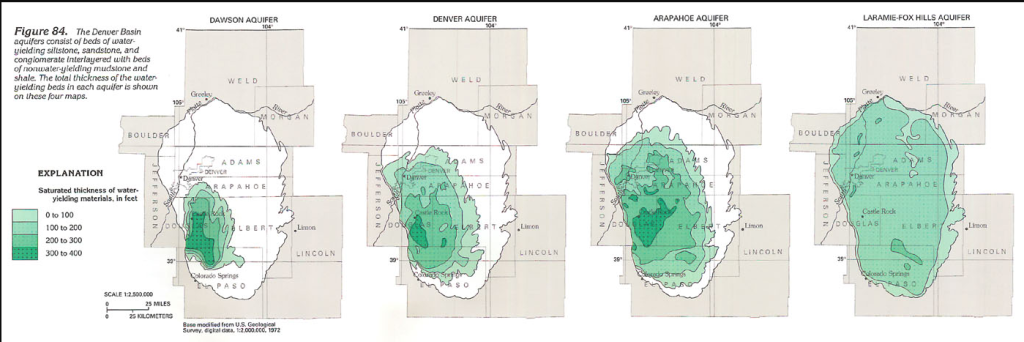

New study says Arapahoe County sitting pretty on water supplies, for now — Jerd Smith (Fresh Water News)

Click the link to read the article on the Water Education Colorado website (Jerd Smith):

November 21, 2024

Arapahoe County has enough water to meet its needs through 2050, according to a new study, but major steps will need to be taken to reduce future demand and protect the county’s groundwater supplies.

Arapahoe County Commissioner Jeff Baker, in a statement, said the study is a cautionary tale, showing that while existing supplies generate 141,000 acre-feet of water each year, future growth could strain those supplies.

“If they want to build, they need to make sure there is enough water to provide adequate water resources to people. This is not a green light to develop,” Baker said.

Arapahoe County is home to 656,000 people, who use 83,400 acre-feet of water a year. By 2050, those numbers are expected to soar, with population topping 900,000 and water demand increasing to as much as 116,000 acre-feet a year, according to the new report.

As with other counties, Arapahoe County does not deliver water, relying instead on 12 separate water districts and agencies to supply its communities, according to Anders Nelson, a spokesman for the county. Some of its supplies come from renewable surface water — primarily runoff from mountain snowpack — while the more rural parts of the county rely on groundwater.

The study outlines several steps that should be taken to protect the fast-growing community southeast of Denver from future water shortages. The county will require developers to document adequate water for new construction projects; implement county-wide water-efficient landscaping rules, and encourage regional partnerships and water sharing agreements.

More by Jerd SmithJerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

#Arizona Governor Hobbs signs historic Navajo-Hopi-Paiute water settlement, sending measure to Congress — AZCentral.com #ColoradoRiver #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the AZCentral.com website (Arlyssa D. Becenti). Here’s an excerpt:

November 21, 2024

Hopi Chairman Timothy L. Nuvangyaoma breathed a sigh of relief on Tuesday as Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs signed the Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Act, a significant step that sends the measure on to Congress. It’s poised to become the largest Indian water rights settlement in history…

“This is a historic moment for the state of Arizona, tribal nations, and all parties to these agreements. They create a consequential and lasting impact by securing a sustainable water supply for tens of thousands of Arizonans and helping local economies thrive,” Hobbs said. “I’m proud to be a part of this solution that many Arizona families have fought to get for generations. It’s a testament to their strength and determination, as well as my commitment to collaborate with Arizona’s tribal nations and protect water supplies for all Arizonans.”

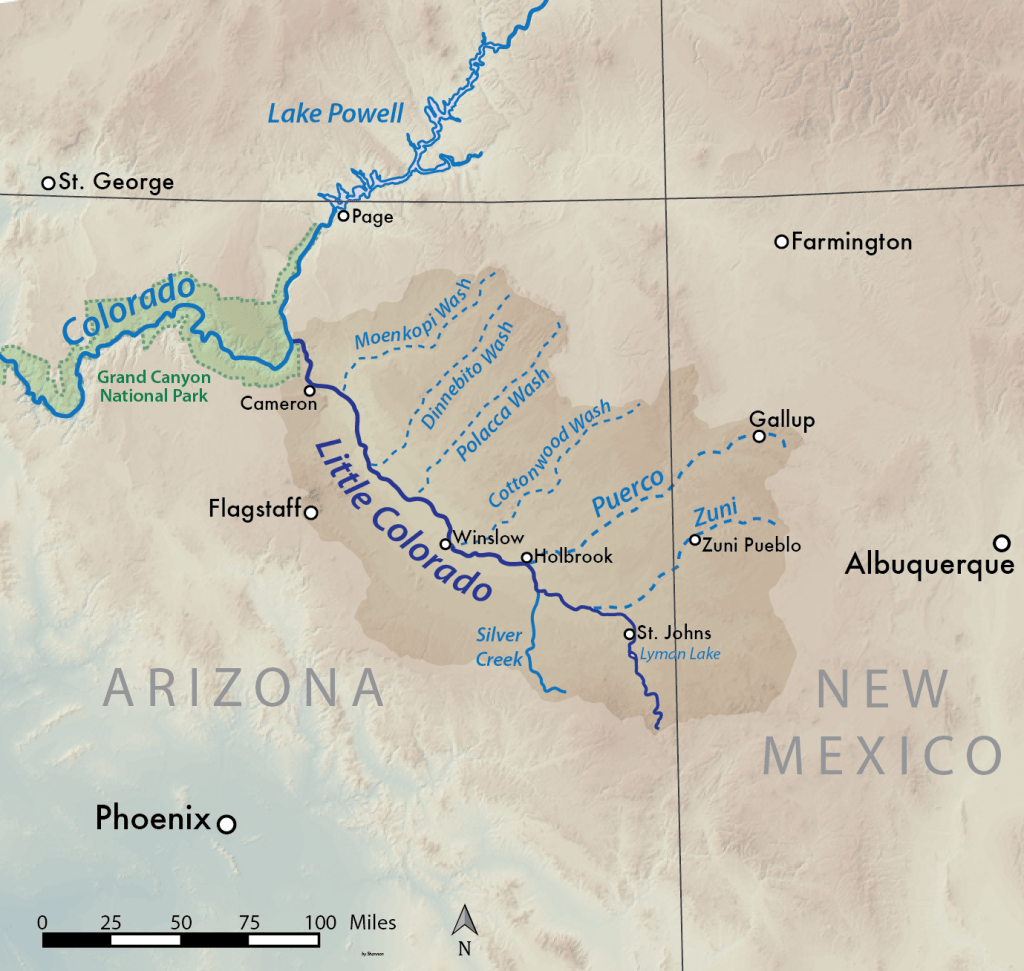

The settlement act resolves long-standing tribal water rights claims to the Colorado River, the Little Colorado River and groundwater sources in northeastern Arizona. The water infrastructure funded by the settlement will address the critical need for safe and reliable water supplies for members of three tribes — Navajo, Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute — ensuring access to clean running water, a necessity all Arizonans deserve…Congress must ratify the settlement before it adjourns at the end of the year. If the measure fails to pass, supporters will have to reintroduce it when the new Congress convenes in January.

Alamosa Riverfront Project: Harnessing the #RioGrande for recreation: Multi-million dollar plan to improve access and habitat on track for 2026 start — #Alamosa Citizen #SanLuisValley

Click the link to read the article on the Alamosa Citizen website:

November 21, 2024

Alamosa is continuing to piece together its Rio Grande recreation puzzle. With support from the city of Alamosa to pull back the levee to make way for a beach, the Alamosa Riverfront Project is taking a different shape. Support from the city will aid in helping bring the project to completion.

During a city council meeting earlier in November, councilors recognized that the project aids in the city’s “Activating the Rio Grande Corridor,” a top priority for the Parks and Recreation Department.

As the river’s oxbow loops lazily trickle ever southward to the Gulf of Mexico, deciphering how to ensure people can access the river, how the river can maintain its natural biodiversity, and how to prevent thousands from losing their homes in a “100-year” flood make it a daunting and sharp puzzle.

The Alamosa Riverfront Project is looking to expand recreation access and improve river restoration from the State Avenue Bridge, upstream of Alamosa’s Cole Park, to the West Side Ditch, downstream of Cole Park. It’s a multi-million dollar project that, so far, has received overwhelming support from the community, according to project planners and members of the community who showed up at a series of summer community meetings.

You may be able to take the town from the river, but the river will continue to flow through town.

The project is looking to connect people back to the Rio Grande, not through adrenaline-pumping white water, but instead by leveraging its natural geographic limitations.

Brian Puccerella, San Luis Valley Great Outdoor’s outdoor recreation manager, has been involved in this project since about 2016. That’s when the conversation about expanding access to paddlers, maybe adding a play wave, and just expanding recreation generally started making the rounds.

The conversation was about “what was possible in our stretch of river in town,” Puccerella said. “We didn’t know the answer to that.”

An engineering study was funded in 2017 to look at what was possible.

“The conclusion,” he laughed, “was not much. It’s pretty flat and we don’t have a lot of flow. That doesn’t mean there isn’t going to be recreational improvement.”

The study equates Alamosa’s stretch of low-flowing river, less than one mile per foot downhill through town, to a “skinny lake.”

Puccerella explained that Alamosa’s portion of the river doesn’t have the flows or drops to ever get whitewater, even in a good year. A lot of the water that flows from the mountains into the river is diverted to different systems throughout the San Luis Valley. By the time the river reaches Alamosa, its flows are quite slow.

What we do have, he said, is flatwater.

That’s not a negative, though. “It creates opportunity for family-friendly recreation.”

Construction is still a ways out. Alamosans can expect construction to begin sometime around fall 2026. A lot of money still needs to be raised, and a lot can happen between now and then. What planners won’t have to worry about is the Army Corps of Engineers’ levee recertification.

BEACHFRONT PROPERTY

When construction is finished, the western levee, the side of the river adjacent to Cole Park, will be pulled back and a highly accessible riverfront beach will be added. Right now there’s a fairly steep, unfriendly drop to the water. In the future, there will be easy access for everyone.

The Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project is heading up the funding and providing the support to engineers throughout the project’s timeframe. During the summer, the group held two community feedback meetings to both inform and learn. From those meetings, project planners were able to adjust the plans.

Final plans will be revealed to the public in early 2025. These preliminary renderings can give us a hint, however.

“We’re doing this because this is what the community wanted,” said Cassandra McCuen, program manager for the Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project. She called the project “amazing and transformative.”

McCuen and Puccerella joined Outdoor Citizen podcast host Marty Jones to talk more about the project and provide updates. You can listen to that episode here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

From those community meetings, project planners were able to incorporate community feedback. Two of the most important pieces of feedback for engineers and designers: ensuring as much of the project is ADA accessible as possible, and making sure the river and beachfront are safe.

Access from Cole Park will be a priority, as it will serve as a kind of hub. The project calls for a few more boat ramps, adding to the two Alamosa currently has. These boat ramps won’t be for motorboats, but personal watercraft such as paddle boards, tubes, kayaks, and canoes.

Increasing recreational potential increases recreational safety. Currently, Puccerella and McCuen said, floating south of Cole Park isn’t advised. The West Side Ditch Diversion and the railroad bridge are a bit of a snag of willows, rusty metal, and splintered wood.

INSIDE THE LEVEE

“Inside the levee it’s more complicated,” McCuen said.

When it comes to changing the levee or potentially changing how water flows through town, you answer to the Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps is responsible for ensuring that levees don’t fail during a proverbial “hundred-year flood.” Alamosa has a history of regular and devastating flooding. The levee system protects Alamosa proper and East Alamosa. Without a certified levee system, property owners are required to pay for flood insurance.

The recertification process is still many years out. The riverfront project is just a few years out. McCuen said the city has been an amazing partner in supporting the project.

With that in mind, project planners were able to meet with the Army Corps of Engineers and provide them with a full rundown of the project, plus the support of the city of Alamosa, and their proposal to pull the levee back.

McCuen said it was a real point of concern, because the project planners were unsure of how the Corps would react to the project’s proposal of pulling the levee back and the inner-levee restoration work.

McCuen said they were finally able to meet with the Army Corps in August. During that meeting, the Corps told the project planners they would be willing to work with them, “as long as you do not impact the flows through Alamosa negatively.”

Pulling the levee back to make way for a beach won’t impact flows in a noticeable way.

“Our project has worked seamlessly with the work that’s gone into levee recertification,” she said.

FISH PASSAGE

People are not only getting an upgrade, but so are the wildlife. This project is unique and special to Alamosa through both its recreation and restoration efforts. McCuen said the attempt is to improve the natural condition of the Rio Grande through town alongside increasing its recreational value. From the planning phase onward, restoration has been at the forefront of the project.

In-town restoration work can be complicated due to the levee recertification, but also due to the geographical limitations Puccerella mentioned. The river is extremely confined, McCuen explained.

Part of that confinement is because the Rio Grande is a very developed river. For example, diverting the Rio Grande’s flow before it reaches Alamosa creates that low flow prime for paddling and floating, but it also makes the water warm.

Warm water is bad for the Rio Grande’s fish. “Super-duper low flows make the area hot,” McCuen said. So one of the major aspects of the restoration portion is creating a safe, cool fish passage.

“We want fish to be able to flow upstream and downstream.”

The fish passage would simply be deeper channels that fish would use as aquatic highways. Also needed are fish refuges, or backwater habitats that exist along the river to serve as places where native fish can take refuge from non-native carp and pike.

Restoring the Rio Grande will take time and effort, but connecting the people back to the river is a start.

“We really wanted to create a project that spoke to the culture of Alamosa, spoke to the community, is something the community wanted, and I think we’re gonna get there because people took time out of their day to be involved in all this,” McCuen said.

#Drought news November 21, 2024: In the areas of heaviest precipitation (1.5 to approaching 3.0 inches), improvement was introduced. This included significant parts of #Kansas, S.E. #Colorado, E. sections of #Nebraska

Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary