January 25, 2024

Click the link to read the article on the Smithsonian Magazine website (Margaret Osborne):

Sitting around a fire at a campsite along the Colorado River in Utah, boater Mike DeHoff flips through old photos of the area. Scientists from the United States Geological Survey circle around him and peer interestedly over his shoulder. He points to an old picture of the North Wash boat ramp, where the group is camped. The ramp was built about 20 years ago as a temporary take out for boaters running Cataract Canyon, a popular section for whitewater rafting, flowing through Canyonlands National Park upstream of Lake Powell. But in the past few decades, the ramp has deteriorated rapidly as water levels receded in the lake and the river here cut away at the land.

DeHoff, a welder based in Moab, Utah, runs the Returning Rapids Project, which documents annual changes in a section of the Colorado river called Cataract Canyon. The project brings external scientists out to survey species, measure sediment changes in the riverbed and examine the geology of newly exposed rock formations. The team presents this information, along with their own observations, to various organizations across the region and to the public. DeHoff and his team do this work, in part, to help provide important information before officials make crucial water management decisions regarding the river.

DeHoff is helping coordinate this March sediment survey with the USGS’s Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center, in a portion of the river that was once part of Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir. In the past few decades, drought, climate change and the overuse of water have caused the lake level to drop, spurring a crisis for the millions of people who rely on it for water and hydropower. But as the lake receded, DeHoff began noticing something unexpected: The river upstream flourished.

DeHoff started seeing changes in Cataract Canyon in 2002—about when the region’s drought started. Lower water levels led rapids to form. Cottonwoods and seep willows sprouted in areas that were once underwater. As Lake Powell shrunk, the river cut through the layers of sediment left behind—dams halt the flow of rivers and stop sediment from moving freely. Yet, despite these rapid changes, DeHoff saw little scientific research or public attention focused on this section of the river. Instead, he says, efforts went downstream to the Grand Canyon, on the other side of the lake.

A brief history

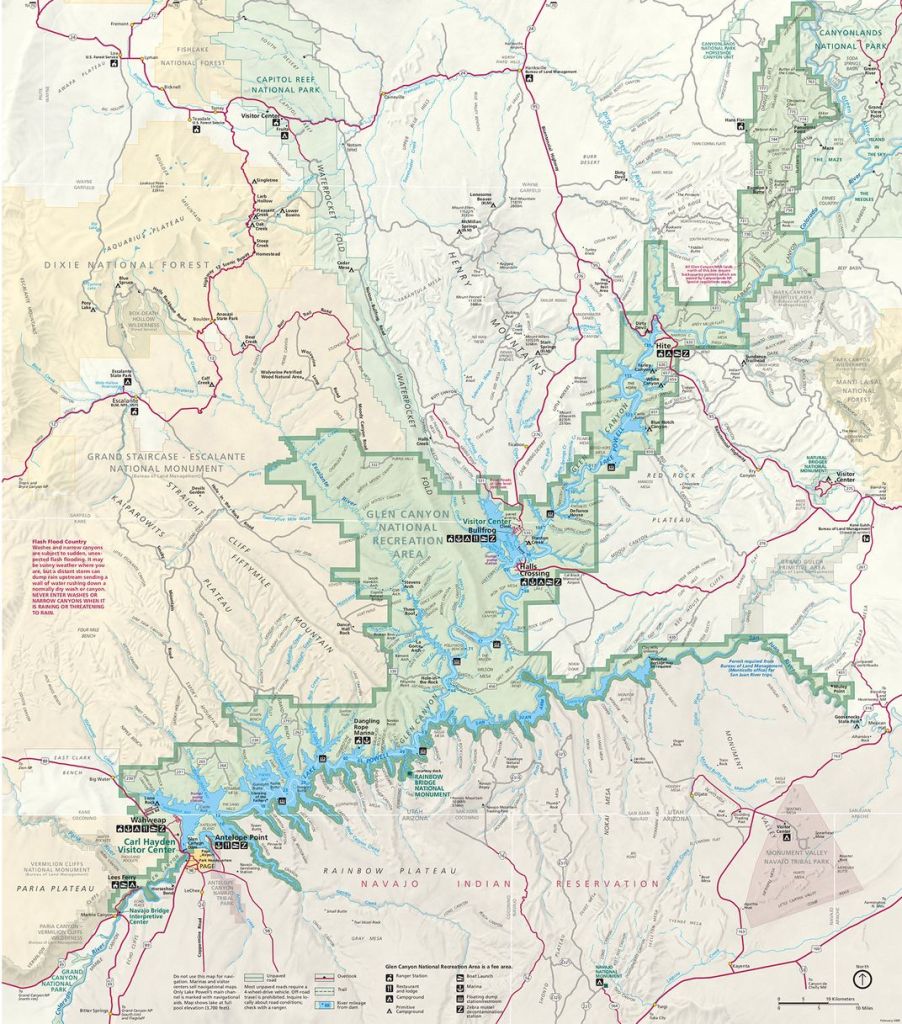

Before engineers dammed the river, Cataract Canyon was notorious for its massive, churning rapids—earning it the nickname “The Graveyard of the Colorado.” In 1964, Glen Canyon Dam was built near what’s now Page, Arizona, to supply power to areas of the West and to form the Lake Powell reservoir. In the United States, the Lake Powell reservoir is second in size only to Lake Mead, which is located 360 river miles downstream.

Seventeen years after the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam was built, the reservoir hit full capacity—or “full pool”—and stretched 186 miles long. It inundated a stretch of river called Glen Canyon, which is sometimes referred to as “America’s lost national park.” The canyon was once home to a variety of plant and animal species as well as unique rock spires, arches, slot canyons and more than 3,000 ancient ruins. Just upstream of Glen Canyon, 65 percent of Cataract Canyon was also flooded, and many of its fearsome rapids disappeared.

The dam has also trapped millions of tons of sediment behind it in Lake Powell, which deprives the Grand Canyon downstream of sand and silt. The sediment holds critical nutrients for life and can form and replenish beach habitats that are important for plants and animals—and campsites for the 27,000 yearly Grand Canyon boaters.

A dwindling supply of water

The West is in the middle of its worst mega-drought in 1,200 years. In just the past few decades, Lake Powell has dropped more than 100 feet. This past March, when the USGS was completing its sediment survey, the reservoir sat at about 22 percent of full pool, just 30 feet above the amount needed to continue producing power.

States, tribes, legislators, the public and other stakeholders are all competing for the dwindling water in the Colorado River, which was originally divided up in the 1923 Colorado River Compact. This agreement among the federal government and Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming was based on science that overestimated the amount of water that would be available in the years to come. And it left Native American tribes and Mexico out of the deal altogether. Over the years, subsequent agreements, court decisions and decrees have been added to the 100-year-old document to determine how water is split up. But at the end of 2026, some of these guidelines governing the system will expire and need to be renegotiated. Experts say deep cuts will need to be made to water usage. It may even mean drilling bypass tubes around the dam, which would essentially drain Lake Powell—one of the solutions the Bureau of Reclamation proposed last year.

The research facilitated by the Returning Rapids Project could help give officials a more holistic view of how their decisions will affect the entire river system. “Everybody knows that there’s going to have to be big decisions made about how we manage the Colorado River,” DeHoff says. “The way we’re using the river, and how we’re storing its water, is outdated.”

Environmentalists have proposed decommissioning Glen Canyon dam for decades to restore the health of the river and help conserve water. Some proponents, including the nonprofit Glen Canyon Institute, advocate to “Fill Lake Mead First,” a proposal that would combine the water from both reservoirs into Lake Mead. The proposal includes the construction of diversion tunnels around Glen Canyon Dam, allowing the river to flow freely through it and restoring Glen Canyon to its picturesque glory. According to a study commissioned by the institute, filling Lake Mead first would save about 300,000 acre-feet of water per year that would have otherwise been lost to ground seepage or evaporation in Lake Powell—about the amount allocated yearly to the state of Nevada. But a 2016 study from Utah State University has put this number closer to 50,000 acre-feet.

Record-breaking snowfall last winter in Utah has caused water levels to rise again. Lake Powell is now around 35 percent full. But scientists caution the drought is not over, and the precipitation is just a temporary fix to the region’s longstanding water shortage.

How the project formed

The shop DeHoff founded, Eddyline Welding in Moab, welds boats, frames and equipment for river runners. Private, commercial, USGS and National Park Service boaters gather there to swap stories and information.

Around 2017 or 2018, Peter Lefebvre, a longtime raft guide, began chatting with DeHoff about his observations in Cataract Canyon. “It was like, ‘Oh, so have you seen this rock sticking out of the river over here?’” Lefebvre says. The two formed the Returning Rapids Project with another local, Bego Gerhart. They wanted to investigate when the rapids would return to Cataract Canyon as Lake Powell receded. So far, they’ve documented the return of 11 rapids.

DeHoff and his partner, Meg Flynn, who’s the assistant director of the local library, have spent hours finding archival photos of the river upstream from Lake Powell. Project members pinpoint where the photos were taken and return to the same spots via raft, by motorboat or on foot to snap images, often at the same time of day and year, to compare the river and the landscape.

“It’s a treasure hunt,” Flynn says. “It’s super fun to figure out.”

The project soon grew, and in 2019, the Glen Canyon Institute, which advocates for a free-flowing river through the dam, took the Returning Rapids Project under its wing, allowing it to receive donations. The project now has four core part-time investigators: DeHoff, Flynn, Lefebvre and Chris Benson, a geologist, pilot and former raft guide. They’ve also recently involved some younger members in research and boat operations.

“All these government offices and agencies were kind of all doing their own thing and not really paying attention to this,” Benson says. “With all this change, all this worry about levels and drought, people weren’t really studying this.”

But scientists have now published multiple papers based on data collected with the help of the Returning Rapids Project.

Returning Rapids has also given presentations to various groups, including the Utah Geological Association, the Utah State University Center for Colorado River Studies, the Colorado Plateau River Guides and classes of university students. They’ve shared their findings with National Park superintendents, decision makers at the Bureau of Reclamation and Utah raft guides. In Moab, they’ve spoken at local events and even given a talk for visiting high school students from California.

The team’s observations, historical research and photo matching are published in yearly field binders for the public to read. Commercial river guides sometimes share the binders with passengers on their trips.

“It’s gone from having a conversation in the welding shop to being a part of meetings of every superintendent who has anything to do with the Colorado River with the National Park Service,” DeHoff says. “And trying to help them think about it, which is nuts.”

In the field

Back at the campsite, the USGS researchers listen as DeHoff chats more about the history of the area. In the morning, the scientists set up equipment and board research vessels, which will collect data on sediment in the riverbank that they can compare to previous surveys.

One boat carries a sonar device with 512 beams to map the floor of the river and a lidar instrument, which uses lasers to scan the riverbank. The team spends the day motoring up and down a section of the river—“mowing the lawn” they call it—near the Dirty Devil confluence. On two computer screens, raw data appears as textured images of the riverbed. “This mossy-colored, brown-looking texture is indicative of sand,” researcher Katie Chapman says, pointing to the screen.

Between 2020 and May 2022, USGS geomorphologist Paul Grams saw the river scour the riverbed 36 feet deeper, and the water is now encountering resistant bedrock. In this section, the river is flowing along a different path than its historical channel. Grams says a waterfall or rapid could form here if the water level continued to drop, which would change how sediment moves in the river and shift the river dynamics and ecosystems upstream. A waterfall could also act as a barrier for migrating fish and affect infrastructure decisions, such as where to build a boat ramp.

As the USGS group mows the lawn, Returning Rapids motors around the river to match photos and measure river depth using a fish-finder device.

In a follow-up survey in the early summer, Grams documented an even more dramatic scouring—about 33 feet in just six months—thanks to the season’s high water flows.

Making a big scientific impact

A few months before this trip, back in the library in Moab, DeHoff pulled out an 11-foot-long map of the Colorado River and laid it flat on the table in front of him. He pointed out areas that have changed over the years. “We’ve seen all kinds of like native flora and fauna come in and repopulate the areas where the river has restored itself,” he said.

Ecologist Seth Arens of the University of Colorado’s Western Water Assessment, who organized the first Returning Rapids science trip in 2019, says the region is a fascinating natural laboratory. Arens was inspired to research the Lake Powell area because of conversations with DeHoff on a private trip. He’s been conducting plant surveys in side canyons and says he’s the first to research the terrestrial landscape that was once underwater, an area that’s about 100,000 acres.

So far, Arens has documented shrubs, cottonwood trees, native grasses, wildflowers, early signs of cryptobiotic soil crusts and unique vertical ecosystems called hanging gardens—all of which have appeared in the last few years. He says this knowledge could be useful for understanding how landscapes change in arid regions as reservoirs dry and dams are removed.

Arens makes it clear he is not advocating for the removal of Glen Canyon Dam, but he says his research should be taken into account when officials make their decisions around future water management. Though he hasn’t published his data yet, he says he’s submitted comments to the Bureau of Reclamation. If Lake Powell refills, it will come at a cost, he adds.

“There will be ecological resources that are again submerged and lost,” he says. “I think it’s fair for that information to be part of that decision-making process.”

Cari Johnson, a geologist and geophysicist at the University of Utah, has also been on several Returning Rapids science trips. She says the Returning Rapids Project has made her research on sediments safer and more efficient. The group has helped her get permits, work with management agencies and provided practical knowledge about boating.

“I wouldn’t be able to do any of the science that I have done so far without [DeHoff],” she says. “He has been incredibly effective at getting smart people all together.”